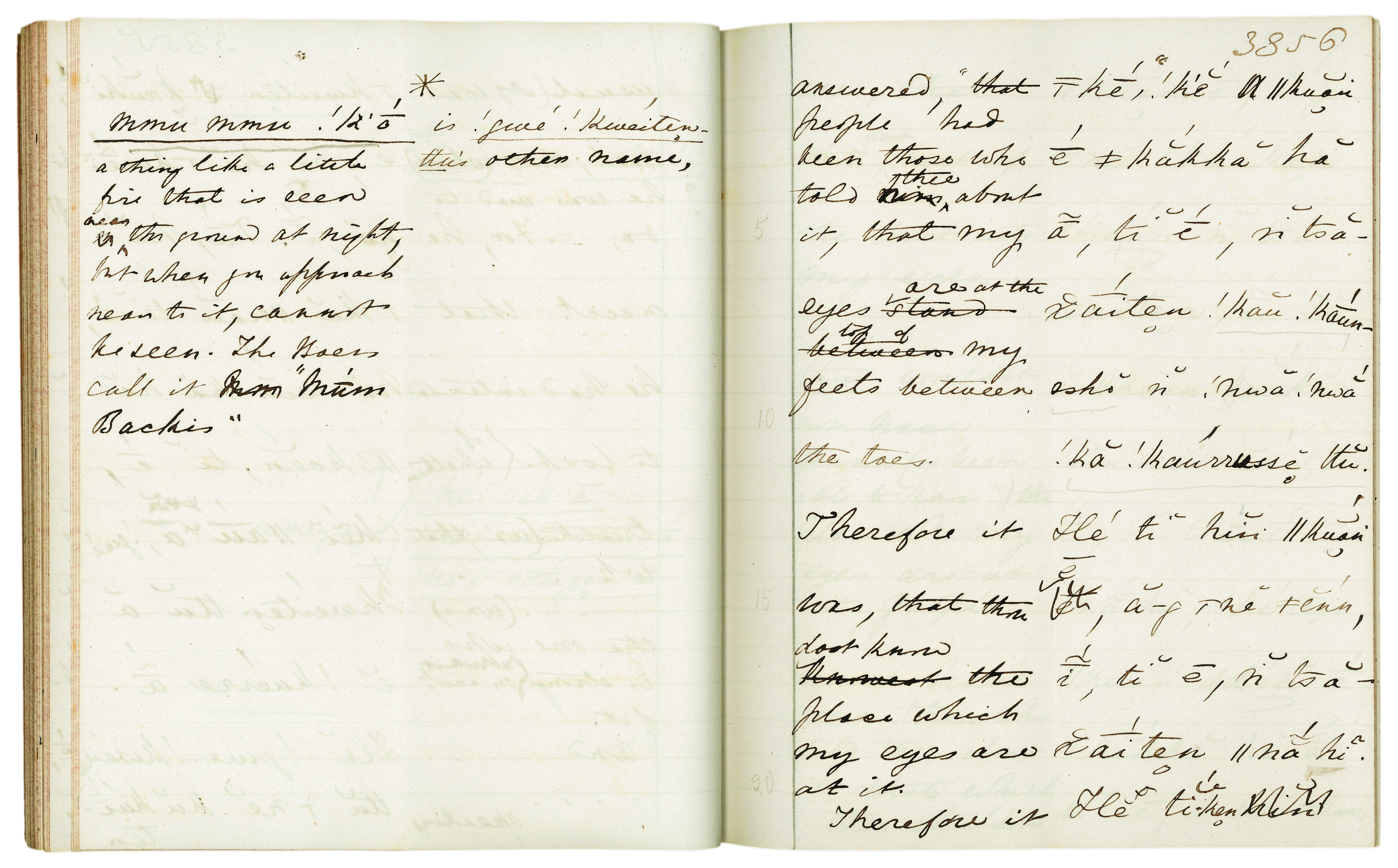

The tracks of Mmu mmu !kō:

digitising the Bleek and Lloyd archive

Curated by Pippa Skotnes

Snowdrops grow on the graves of Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd. Each August, in the anniversary month of both their deaths, I visit the graves in the small Anglican graveyard in Mowbray. It is unvaryingly cold, and often raining, but there are always, in places, white snowdrops budding in pretty clumps amongst the roughly cut patches of grass. In 2014 I visited the graves with Janette Deacon and Patricia Davison and was surprised and delighted when, some weeks later, Patricia gave me an envelope inside of which was a small folded sheet of paper containing several pressed and dried flowers she had gathered on that day. They were snowdrops. Patricia’s gift was a gesture that would serve as a keepsake of our visit, but it was much more than that, since it mirrored, with generous deliberation, the same impulse to retain a token, a memento, indeed a relic of sorts, expressed by Helma Bleek when she visited her father’s grave 130 years before us. Her pressed snowdrops, and mine are now part of a growing collection I have, which is, in a large part, the residue of the two decade-long programme of the digitisation of the Bleek and Lloyd Archive. These snowdrops, and various other objects such as cardboard index-card boxes, shoe boxes, a blue bone folder, a grey hair and a silver key, are current residents at the Centre for Curating the Archive, at present adrift from the main holdings of the collection, yet significant, I suggest, in helping us think about the all important process of making an archive, and the importance thinking about the nature of both digital and post-digitised collections.

I first encountered the Bleek and Lloyd Collection when I began to read the notebooks in the Jagger Library in 1988. At that stage very little was known about it and only a small portion was available in publication, including Lucy Lloyd’s edited collection Specimens of Bushman Folklore (1911) and several essays in the journal Bantu Studies published by Dorothea Bleek. I was aware that a microfilm copy of some of the notebooks existed and had been used by David Lewis-Williams and I was also aware of the presence of Janette Deacon who had worked her way through the notebooks, and embarked on her project to find the home places of the |xam language instructors. The contents of the notebooks totalling over 12000 pages were not yet described and the extent of the dictionary was unknown. There were pockets of the collection in several different institutions, some of which had not been listed, and there were still significant collections of letters, notes and photographs held by the descendent families in different parts of the world. The distribution of the collection also reflected divisions that existed in archival and object collecting practices, so that things to be read seemed to have been consigned to libraries whereas things to be seen (such as maps, drawings and objects) went to museums. The South African Museum, for instance, holds Bleek’s daughter, Dorothea Bleek’s field collections and many of the inherited drawings and watercolour sketchbooks, as well as small clay sculptures and other things made by the young !kun boys who lived in the Bleek household in the 1880s.

As I worked with the collection in the 1990s it began to become clear that emerging and improving opportunities to digitise would allow for the assembling of the whole collection in one place. Furthermore, one of the central language instructors, ǁkabbo, had indicated his desire for his stories to be known to future generations by way of books, and the idea of realising this ambition on the World Wide Web was an exciting prospect. In 1995 I bought my first Apple Mac and scanner and, over the next five years, developed facility and understanding in both layout, scanning and Photoshop programmes. By 2003 I had raised the funds to begin to digitise and conserve the collection (significant parts of it falling victim to age and disintegration) and introduced the topic to our library at UCT.

Initially my proposal was met with reluctance. At this time digitising large archives was in its infancy, and in South African there was nothing to compare to the scale of the project I was proposing. Even as we agreed that all work would be done in the library and that all risks to the collection would be minimised, there remained a lingering resistance to the idea of easy global access to the collection. Indeed, at first a condition of digitising was that there never exist more than 10 copies of the hard drive or CDs and that these would be lodged in the UCT library. The concern seemed to be that Internet access would diminish the value of the library itself, that visitors and scholars would cease to visit the library and that in such an atmosphere the physical library or archive would become beleaguered and its holdings placed at risk. Indeed, a real worry was that a separation of the information from the object would render the object irrelevant, and would divert attention from the institution in whose care the objects resided.

Despite these worries the project to digitise the collection began, first with the |xam and !kun notebooks, then the maps, drawings and watercolours. This involved the University of Cape Town, the National Library of South Africa, Iziko South African Museum and UNISA where several Korana notebooks were housed, and require formal agreement from these institutions. At the same time my grant allowed us to conserve all the material on paper at UCT, making cases for the books, and sleeves for the genealogies, drawings and maps. This work was undertaken with the assistance of Eustacia Riley and later Thomas Cartwright, with Fazlin van der Schyff operating the scanner, and we were also able to assist with the cataloguing of the drawing and watercolour collection and conservation of George Stow’s maps at the National Library.

In 2005 we launched the Digital Bleek and Lloyd as a website and shared the high-resolution scans with the three participating institutions. The tagged information attached to each scan amounted to a 250 000 word index which still remains the primary (though subjective and often inadequate) way to search the notebooks. Initially a searchable index seemed almost impossible without enormous resources, but a local (and lasting) solution was found by a young computer scientist Hussein Suleman1.

at the University of Cape Town which also enabled the production of an interactive DVD included in the 2007 publication Claim to the Country 2.

The possibilities and, indeed the poetics, of an online collection, allow for a more expansive way of thinking about an archive. In a 2014 publication I and my co-editor Carolyn Hamilton3 deployed the term curature to describe intersecting sets of activities relating to archives which suggest not only the care, organisation and ordering of collections, but the active curatorship of them more usually associated with museums, and indeed, with artists. In my own case, the digitising of the Bleek and Lloyd collection facilitated forms of custodial care (through grants to preserve and conserve), as well as forms of curatorship as aspects of the digitised record were mobilised in exhibitions4, publications5, and other kinds of performance6. Indeed, The Centre for Curating the Archive7 (of which I was the founding director), engages in activities intended to destabilise conventions of the archive, encouraging interdisciplinary activity around collections, insisting on a more inclusive idea of what constitutes the archive itself. Thus, in the digital Bleek and Lloyd, objects entrusted to the museum are brought alongside documents consigned to the library, insisting that objects can be archival, and texts can be both images and things. Further to this, the possibilities of the digital archive allow for the inclusion of new material – both material not at first deemed to be part of the original collection, and material which comes to be so closely associated with the original collection that it is later deemed to be part of it. Hence the digital Bleek and Lloyd now includes, for example, the collection of rock art copies made by George Stow by virtue of the fact that it was owned by Lloyd (bought from his widow after Stow’s death)8, and aspects of the land itself – both archaeological and historical documentation (first identified by Janette Deacon) that provide context to the lives of the language instructors and their stories. The digital archive is, therefore, able to evoke distant contexts, and convene material in the ether while the objects themselves remain in the custodial care of their home institutions.

Receipts from Mrs F L R Stow, widow of G W Stow, for her husband's drawings and manuscript of "The Races of South Africa", bought from her by Miss Lucy Lloyd, 1882-1883 and 1885

The fire at UCT in 2021 became the next major impetus to edit and publish on line the balance of the UCT collection of the archive. Money was raised by the university and private donors offered support9. While the majority of the collection was saved from the fire, several hundred photographs and other documents were incinerated. I was able to assemble a team who from 2021 continued the task of scanning, creating metadata and collating the collection that was begun in the early 2000s10. In addition, in this iteration of the Digital Bleek and Lloyd, I have presented the archive as both an edited collection and a series of curations. In editing this website, I have been alert to the fact that convening the material, creating its metadata, categorising its content and creating internal taxonomies are not neutral acts, nor are they free from elisions and personal preferences. Some parts of the archive will be drawn into bright light, others will lurk in its shadows. To mitigate this, to some small extent, I have solicited and included a number of digital curations. Various scholars have generously contributed short visual essays that introduce aspects of the archive11 and other more substantial curations have also been added. 12

One of the most important concerns of this project has been the ethical issues relating to its central figures. These include, on the one side, the two scholars whose initial desire was to document the ǀxam language, and on the other, the language instructors who, at first served time, and then later freely gave time, to teach Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd their language. Much has been written about the history of this language learning project and scholars have grappled with both the inescapable legacy of colonial power that haunts the archive, and the astonishing presence of collaboration between people of deeply differing experiences. I have often imagined the scene as ǀxam-speaking man ǁkabbo, dislocated from his place and family, sat opposite English-speaking woman straining to discriminate the cadences of his language and translate his ideas. Was he unwilling, gradually willing, or as he says, keen for his language and stories to become known by way of books? Or did he see it as an intellectual challenge, a means to breach the gulf of misunderstanding that had condemned his people to lingering death. I imagine his struggle against her incomprehension … how do I make her understand the nature of !gwē – perhaps she will understand if I explain it is like the letters she receives when the mail boat arrives… and colour terms … what is this she wants? Why should we name a hundred shades of rock and flowers red?13 I imagine his visits to the South African museum to give animal names. Who are these people who kill animals to stuff their skins, do they not know that even these have language and a place to which they will go, along with all people, when they die? The many ǀxam, ǃkun and others who acted as language instructors and intermediaries between their own oral and performative culture, and the writing and publishing project of Bleek and Lloyd were, without doubt, in, what Louis Anthing called, a fight with death. Their food sources had been depleted, their land occupied and resistance resulted in prison or massacre. If arrested their only choice left was to maintain a silence or tell their stories, and for some, Bleek and Lloyd offered the latter as an option. In thinking through the ethics of this project, my choice has been to do what I could, though books, projects, exhibition, conferences and web publication to make their stories known and their sacrifices worth something.

The ethical worries of working with Bleek and Lloyd’s contribution has been of a different kind. On the one hand this archive includes many personal letters divulging private longings and fears. Some they may never have wanted published. They also expressed ideas and made comments that, on the face of it, seem unacceptable, or prejudiced. None of this material has been edited out of this web publication, but it is presented with the request that readers realise that just as the fate and legacy of the ǀxam and ǃkun instructors was altered by Bleek and Lloyd, so too did Bleek and Lloyd undergo a transformation of understanding as they worked with them. WHI Bleek of the 1860s was not the same man as WHI Bleek of 1875, and Lloyd, as first the assistant of her brother-in-law in trying to comprehend what she thought of as the most alien of languages in 1870, was able, in 1878, to write of the all-important work of recording the literature of indigenous people in their own languages and its role in a fuller understanding of what constitutes humankind. We are not alone dwellers in this country, she wrote, and much of her life after Bleek’s death was devoted to sharing these insights.

Perhaps the most unanticipated aspect of digitising this collection is the problem raised by the leftover. Conserving, for instance, the original dictionary in the Bleek and Lloyd archive, resulted in the rehousing of the thousands of slips in acid free casings and replacing the old foxed and decaying index card boxes of Wilhelm and Lucy’s era, as well as the shoeboxes later used by Dorothea Bleek. While the library did not want to keep these old boxes, I was less sure that they should be discarded and so have kept them. Similarly, a blue bone-folder, used to apply pressure when gluing definitions to cards, found in one of the index card boxes, as well as a grey hair, which may or may not have belonged to Dorothea Bleek or Lucy Lloyd, have been added to this collection of left-overs. For me these objects are powerfully connected with the inception of the archive and a family of gestures and activities. The bonefolder alerts us to a process nowhere else mentioned in the archive, and every time I use my own bone folder, I better understand the physical making of the Bleek and Lloyd dictionary. Similarly, the |xam and !kun themselves made objects as part of the work they were doing at the Bleek house in Mowbray. These included musical instruments, arrows, and clay sculptures. Some of these are in the South African Museum and the Kirby Collection, others are at Wits or in European Museums such as Musée du quai Branly14. The things, objects of significance in their own right, are also left-overs and are able to conjure the presence and activity of their users and makers.

The problem of the leftover is reminiscent of the fierce early modern debates in Europe about the nature of the Eucharist and the residence within it of the body of Christ. Catholics believe (as they did then) that the host actually becomes the body of Christ and is ingested in that form by the supplicant. The reformers, however, were keen to liberate Christ from the messy carnal fate of the digested host, making his body only symbolically present at the ceremony of the Eucharist. A similar choice exists for libraries today: should the leftovers of digitisation remain inextricably part of the archive, and thus present new problems for custodianship and interpretation, or should archives in a post digitisation world be liberated from their increasing and seemingly irrelevant objects, in their second lives in the ether?

Put another way: what are the ethics of digitising, and does the status of the archive as matter have continued value, and if so, what is that value and what questions arise as a result in terms of its “curature”. The concerns of the library when I first wanted to digitise the archive were concerns rooted in an understanding of manuscripts and documents as information. The discarding of the shoeboxes, and the limbo in which the bone folder and the grey hair exist in my collection of left-overs, all point to the persistence of this idea. Unlike the letters and the notebooks, these objects do not immediately declare their ‘content’ and so escape custodial attention, and care. But in a post digital age, the whole of the archive has become left over, its information liberated from the material that once held its content captive. In creating this digital version of the archive, I have been alert to the creation of yet another way to evacuate the vitality of the original oral testimonies and the ‘real presence’ of the objects, but I have also seen their ‘undeclared content’ as content brimming with possibilities. Similarly, I would argue that the mass of connections possible in a digital site, imbricated as it is into a world wide web, produces a different set of possibilities, some anticipated and many serendipitous, which point to another kind of vitality which can live separately but alongside the stuff of the material archive. This website will, hopefully, in using it, demonstrate how.

This brings me back to the snowdrops that grow on Wilhelm’s grave, first pressed by Helma Bleek as a young girl for her scrapbook in the 1880s and then by Patricia Davison for me just a few years ago. When I look at these pressings, separated by 130 years, I am powerfully reminded by how objects both become the survivors of past times and how in the present they collapse time. Just as the ceremony of the Eucharist brings the faithful back to the moment of its inception, the snowdrops bring me into the presence of Helma at the grave all that time ago. I see her and Lucy Lloyd, walking arm in arm along the little path towards the white cross which marks her father’s final resting place. I see her picking the flowers, and I imagine Lucy describing something or other of the father she never knew. I see them both standing right beside the snowdrop-filled plot of earth that would one day be Lucy’s grave. These pressed flowers have an enchanted kind of agency, for they suspend time, even as they remind me of the time that was to come, all the time that has now passed. They bring me back into the present of the past and they offer me my continuity with it. While all that may be found in this space is not yet clear; we are surely offered an opportunity to look around and see the things the archive of written words did not and cannot record. Such opportunities, I would suggest, will involve the assessment and appreciation of the materiality of archival and object collections, and a reappraisal and valuing of the leftovers once conservation or digitisation has taken place. This may require a re-imagining of the physical space of the library and a different kind of curating of the archival holdings. But it also insists that those of us creating digital archives find ways to include and evoke and conjure the material of the archive itself.

In the |xam lore there is character called Mmu mmu !kō described by Dia!kwain as “a thing like a little fire that is seen near the ground at night, but when you approach near to it, cannot be seen”. Lloyd translated his name as Will ‘o the Wisp15, which was thought, in English lore, to be a ghostly or shimmering presence hovering above wet places – a kind of sprite trailing a wisp of light (and later understood to be a phosphorescence produced by rotting vegetation in marshy places). Mmu mmu !kō, however, left a spoor, leaving physical tracks that were the left overs of his presence and activities. This digital archive tries at once to track the spoor of the archive, even as it presents it, inevitably, as disembodied and spectral, and drifting on the wind.

Pippa Skotnes was born in Johannesburg. She attended high school at Parktown Convent: the order of the Holy Family. This experience provided a well-spring of ideas, some of which materialised in her continuing artwork, Lamb of God and the Book of iterations (2001-2011), which has been exhibited in South Africa, Europe and the USA. She was educated at the University of Cape Town where she received Master of Fine Art and Doctor of Literature degrees. After she was sued by the South African Library for a copy of her artist’s book about Lucy Lloyd and the |xam, Sound from the thinking strings, she became deeply interested in the nature of the book, producing several volumes inscribed on the bones of horses, leopards and blue cranes. She has also published a number of other books, more recently Claim to the country (Jacana 2007), Unconquerable spirit (Jacana 2008) and Book of iterations (Axeage Press 2009) and exhibited artwork widely. She is currently professor of Fine Art and the director of the Centre for Curating the Archive at the University of Cape Town, where she is working on a project about land and language, and holes in the ground.