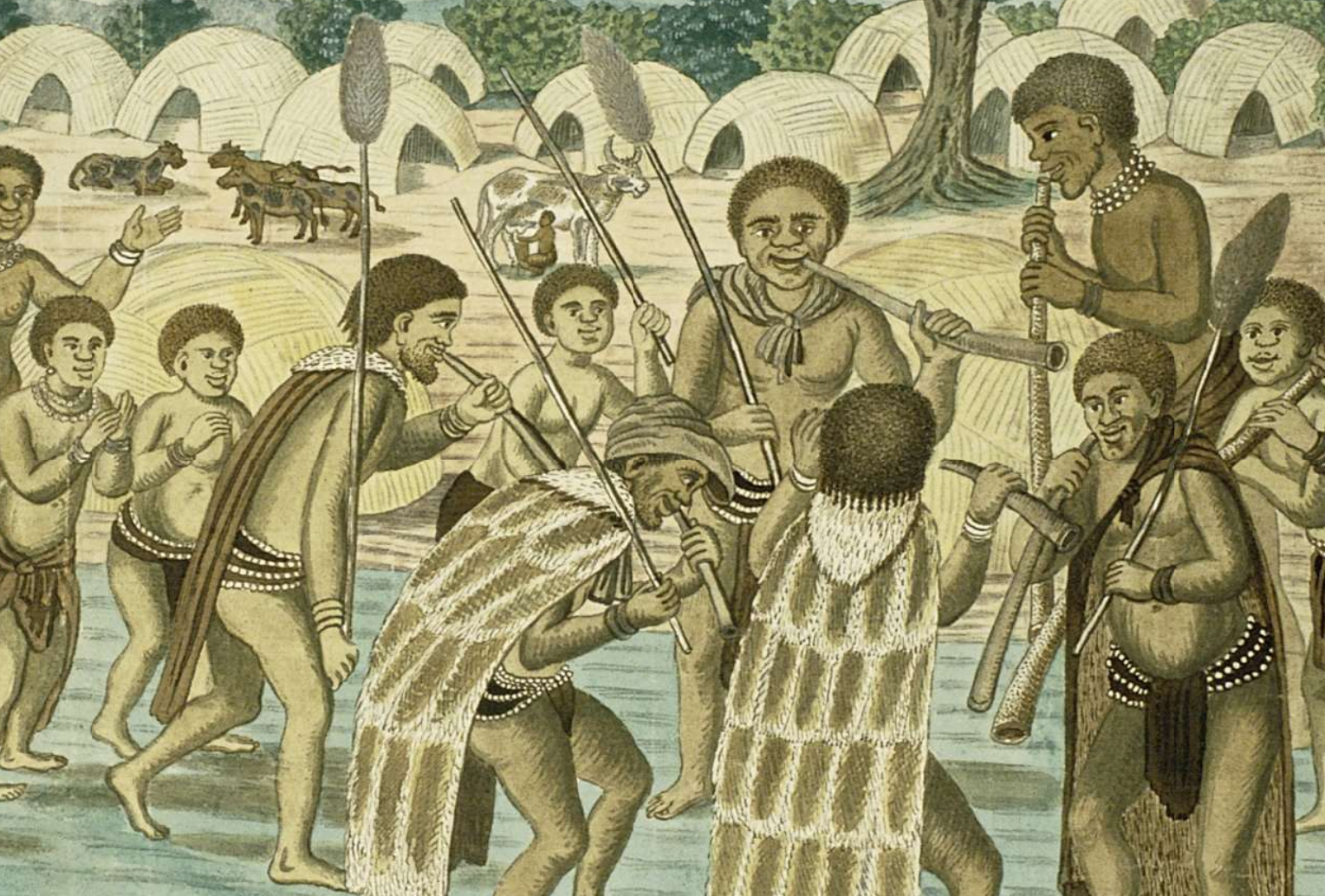

Flywhisks feature often in the rock art of southern Africa. The rock engravings of the Upper Karoo, in the Northern Cape, made by the ǀxam people and their ancestors, are no exception. The ǀxam narratives recorded by Bleek and Lloyd tells us how these objects were made and of what materials. The stories also indicate that their use and significance went well beyond their utilitarian function of ‘wiping the face’ to remove sweat.

Flywhisks (also called fly-switches) are present in the rock art and kukummi (singular kum, ‘stories’) of the ǀxam of the Upper Karoo. Dorothea Bleek’s Bushman Dictionary (p. 472) gives ‘brush, feather brush, made of the tail hair of the caama fox or of grass, used for wiping the face’ as the English for ǃnabbe, indicating that there were several types of flywhisks, made of different materials. Another term for this artefact is ǂhaξrri-he, which Dorothea Bleek’s dictionary (1956, p. 650) describes as ‘feather brush used as pocket handkerchief, ostrich feathers tied to a stick and used to wipe the eyes’.

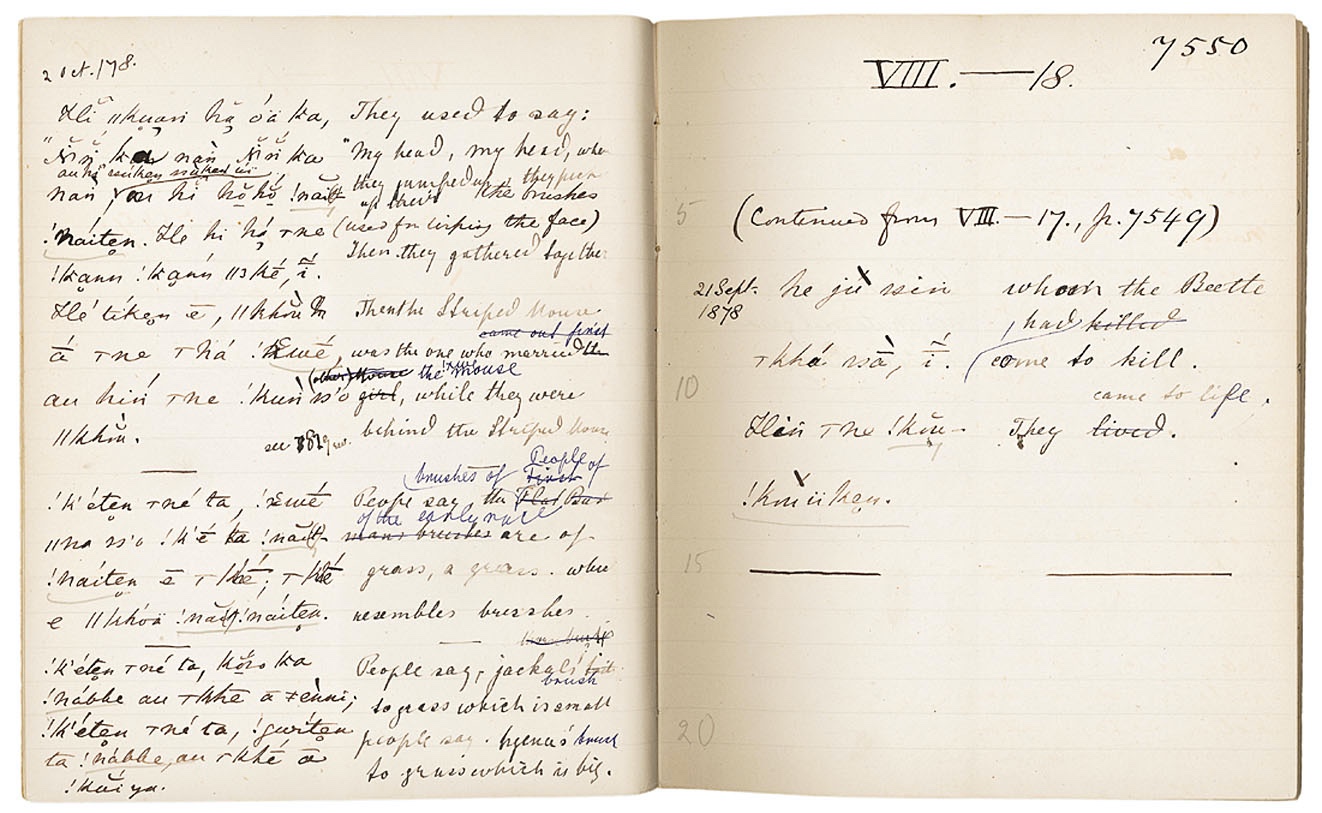

In an unpublished gloss to the kum ‘ǃgaunu-tsaxau (the son of Mantis) the Baboons, and the Mantis’ haŋǂkass’o told Lloyd about the ǃnabbe, a flywhisk made with animal hair1.

According to him, the ideal material to make a ǃnabbe was the “flowing tail” of the ǁwa, that is, the caama- or bat-eared fox (Otocyon lalandii). The ǀxam used the whole of the ǁwa’s tail, but not before heating it to prevent decay. Other animals mentioned by ǀhaŋǂkass’o in connection with the making of the ǃnabbe are the jackal (koro, Canis mesomelas) and the Cape fox (ǃgwiten, Vulpes caama), whose tails, however, are considered ‘ugly’. The handle of the whisk was made of the twig of a driedorn (ǃnabba, Rhigozum trichotomum), a bush very abundant in the part of the Karoo where the ǀxam lived.