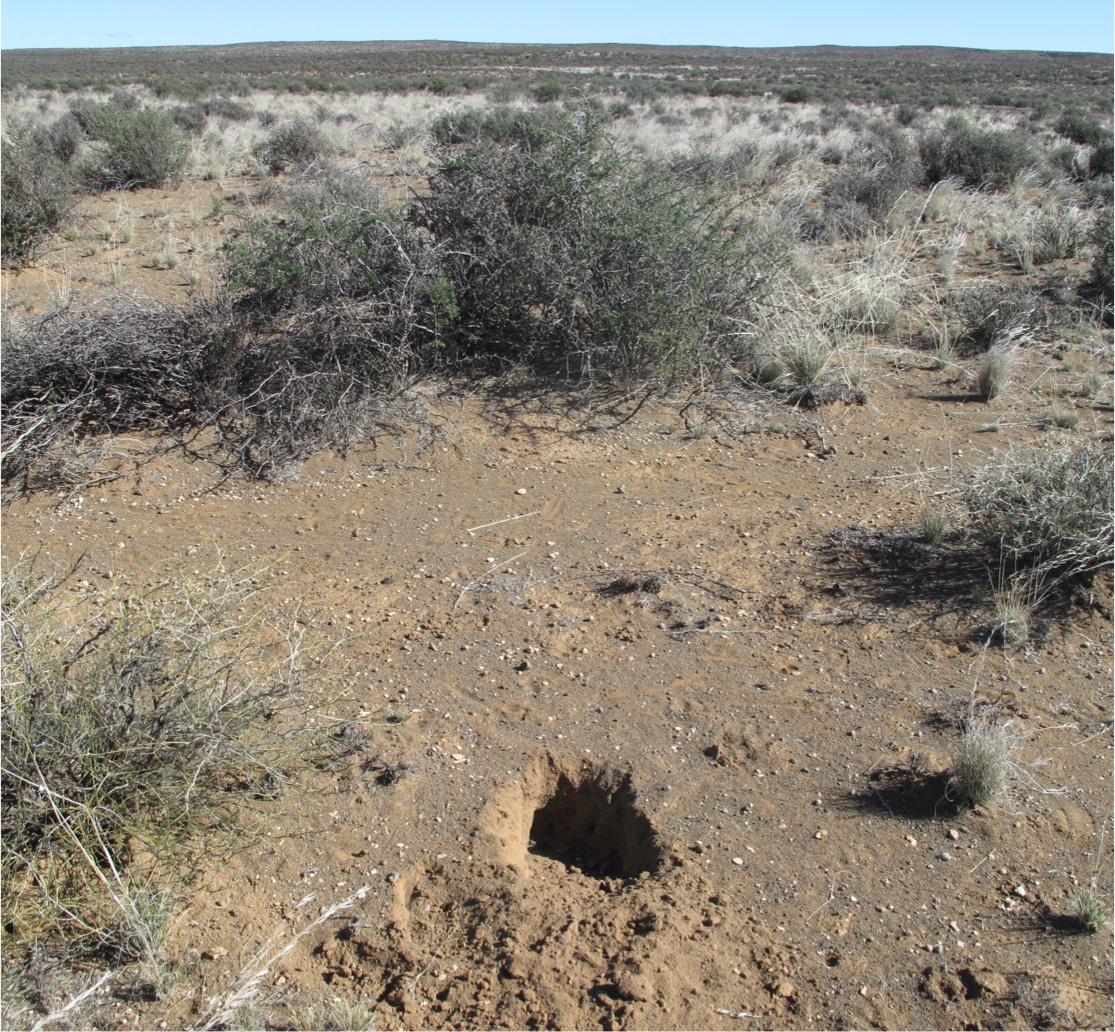

Anteaters (or aardvarks) were animals who lived between two worlds, the world below the ground and the world above. In ǀxam thought, the anteater also exerted influence at the time when the order of things was established. The Anteater’s Laws, which is also the title of a central story in ǀxam lore, were laws that determined the proper food for different animals and their appropriate behaviours. They signalled the end to the early time and the beginning of the later order of the world.

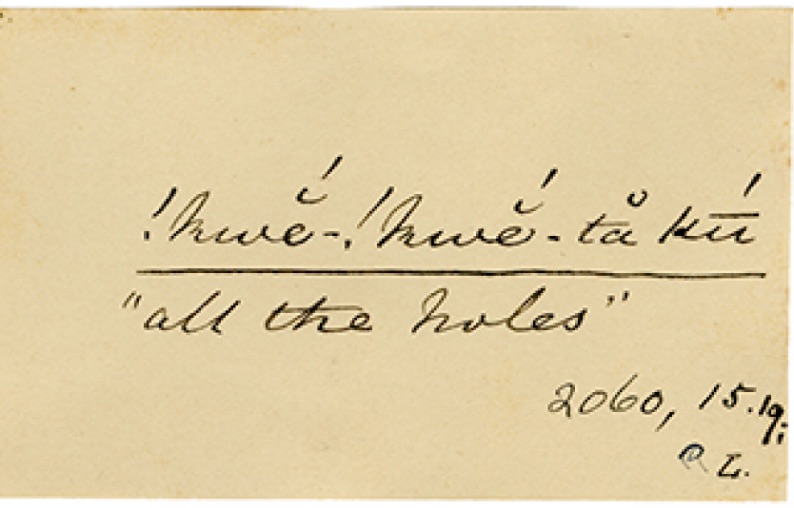

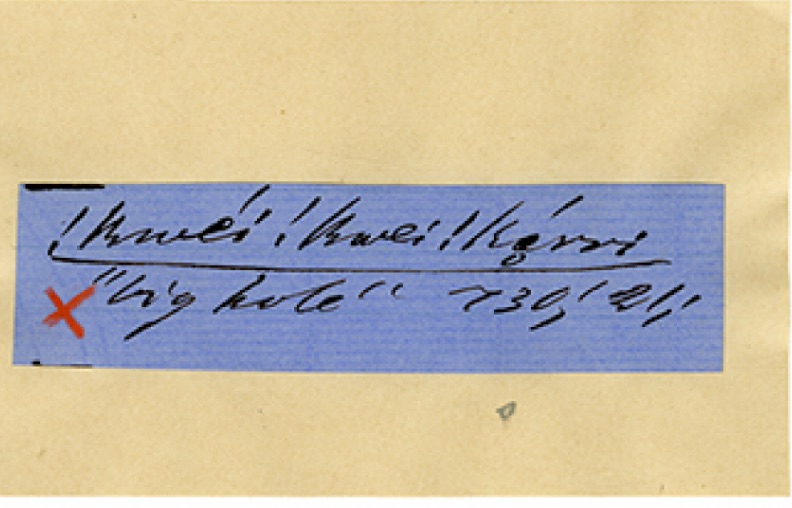

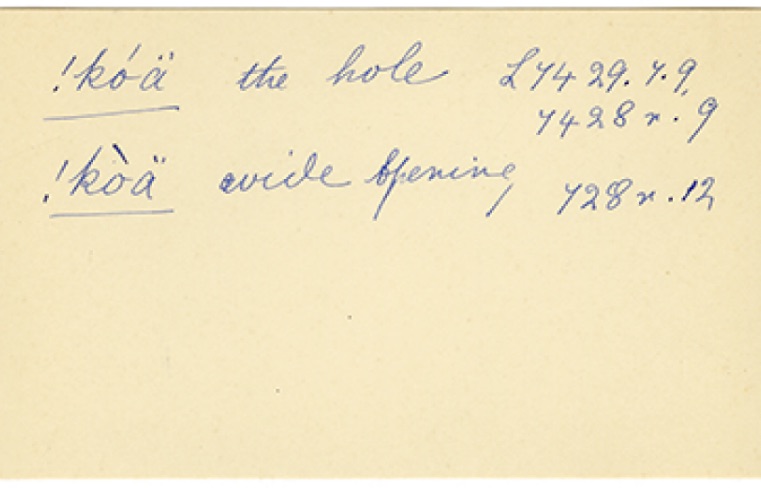

A rich language exists to describe holes. The ǀxam dictionary created by Bleek and Lloyd demonstrates this with English translations for, amongst others, a hole, a little hole, a big hole, a great hole, the hole made by a digging stick, the ground of the hole, the hole’s house, the hole’s inside, the making of a hole, the hole above the nape of the neck and the hole at the lower back of the head, holes between the toes, a great hole’s house, the den’s big hole’s inside. The hole has a neck and a throat, it has an inside. A hole has, at times, unfathomable depth. ǁkabbo told of the great hole to which all went after death and burial and lived there, no matter who or what the cause of death2. For nineteenth-century ǃkun, holes were the day-time residence of stars3. Holes found in rock that fill with water are called the ǃhun. There are names for waterholes that are made in sand or surrounded by bushes. Waterholes are places where girls taken away by the Rain have become like beautiful waterflowers; these will not allow themselves to be plucked and disappear when approached. They become the water’s wives. Stars fall into waterholes, and they are also the home of the spirits of the dead4.

I make my house of a hole: for I am an anteater.

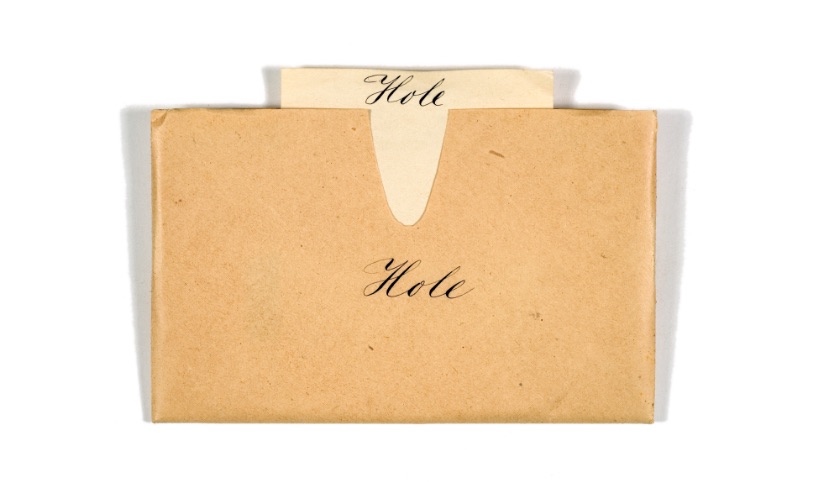

The manilla envelope into which the entry for holes are inserted.