People from many small and deeply rural communities have to be self-sufficient, but few more so than tiny indigenous communities who live entirely off the land in challenging environments, just as the ǀxam and their ancestors did in South Africa for so many thousands of years. When thinking about people like the ǀxam, it is common to talk about their skills of hunting or fire making or their extremely impressive knowledge of animal and plant resources. What is perhaps less talked about is what else it takes for them to live successfully, relying only on the attributes of twenty or so people in their group and the natural resources around them.

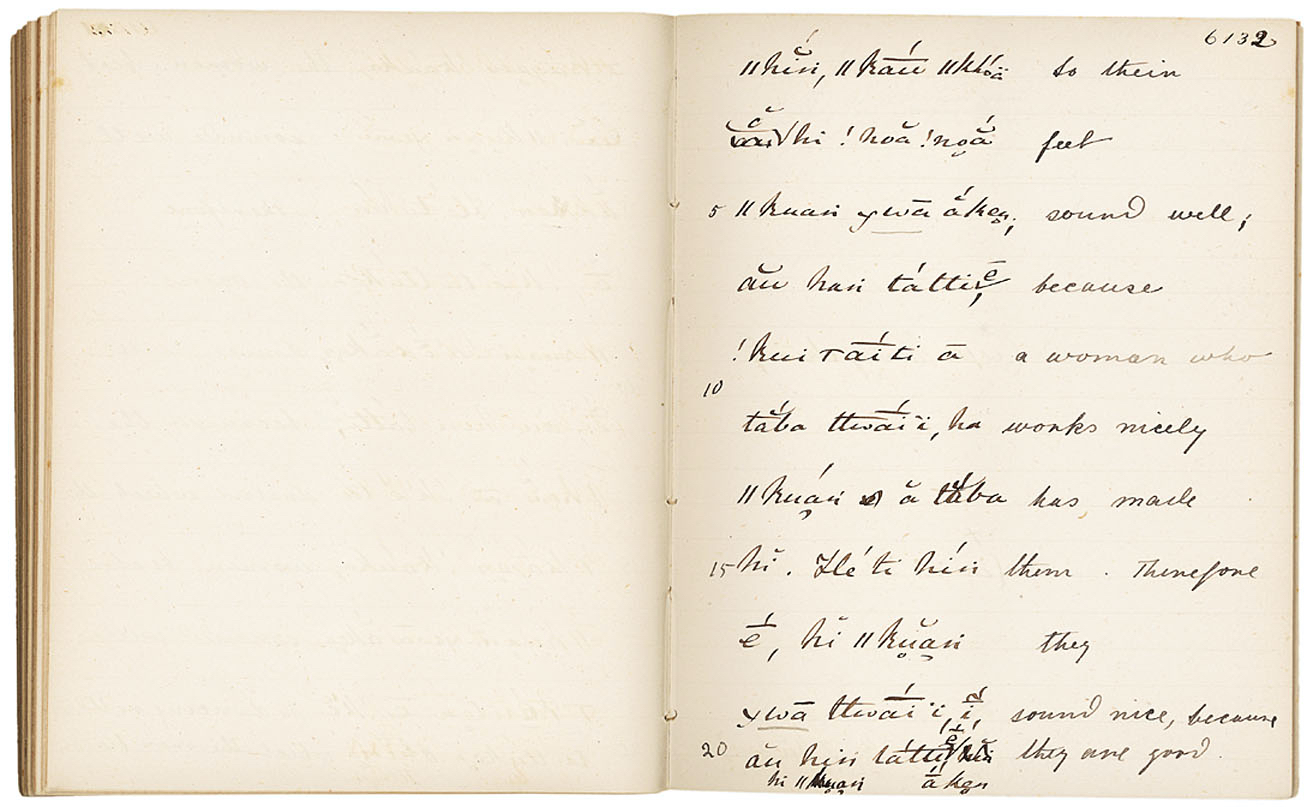

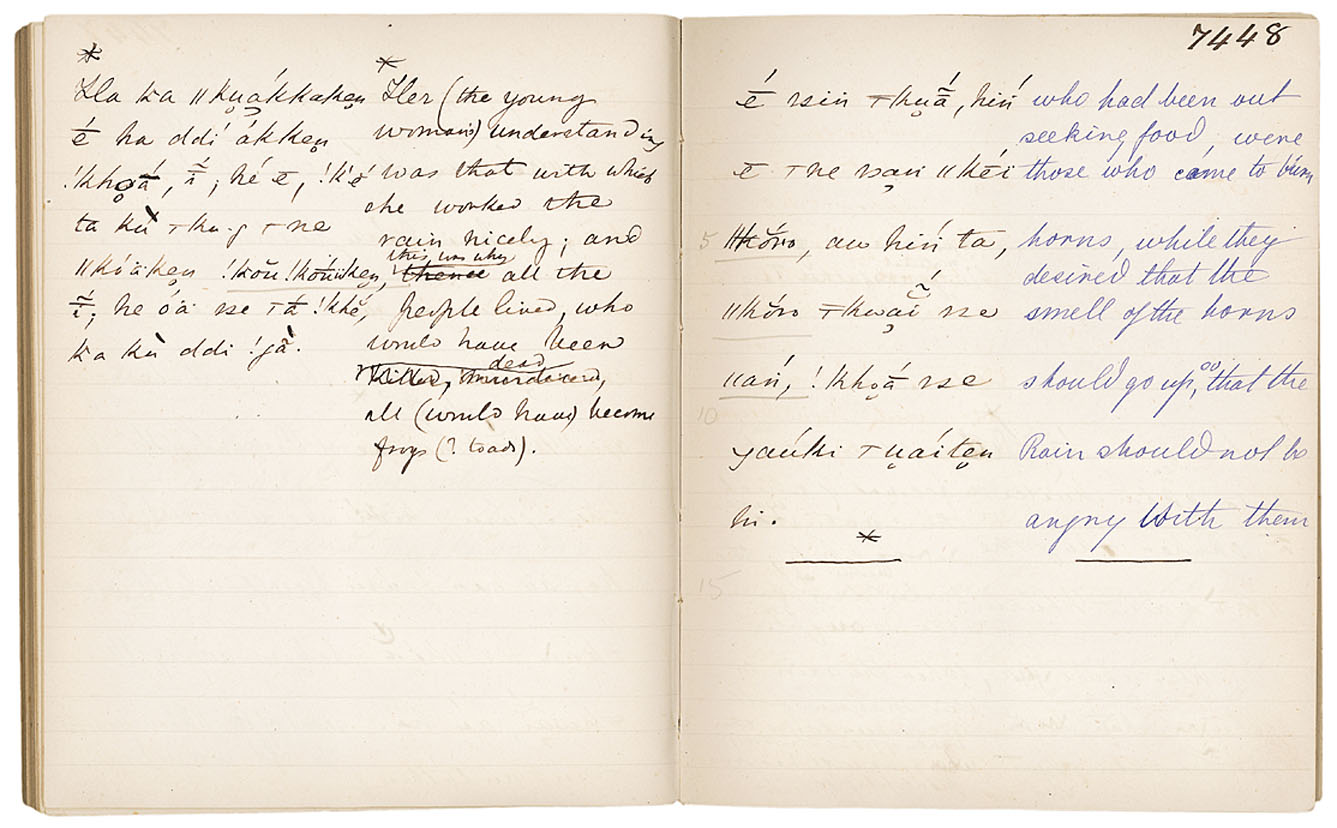

There is an English word that features repeatedly in the Lloyd and Bleek archive which leads us to a more rounded and subtle way of thinking about what it takes to live as the ǀxam did, and indeed about what is involved in making our own lives more or less successful. That word is ‘nicely’, a word principally significant to many English speakers simply for its lack of significance. Many English speakers will have been taught from an early age that they can use a better, more meaningful and less lazy word than ‘nice’ and, by implication, the adverbal form ‘nicely’. Given this abhorrence of the word, it is intriguing that it persistently crops up in San material translated into English from such diverse San languages as Afrikaans, Juǀ’hoan to Gǀui.