Description

Dorothea Bleek noted, in the first part of her “Bushman Grammar” (1928/29: 86), that:

In my MS Bushman dictionary there are three and a half boxes of words without clicks, seven and a half of words with clicks. Of these, two boxes hold words with ǀ, three hold words with ǃ, two hold words with ǁ, while the words with ǂ and ʘ share half a box between them.

The slips filed in the eleven boxes mentioned by Dorothea Bleek appear to have been essentially the same set of notecards as those now digitised and presented here.

The collection was clearly intended as the basis for a ǀXam dictionary, yet there are occasional instances where Dorothea Bleek has intercalated a word from some other ǃUi language, such as the Langeberg (Nǁng) variety which really formed part of the Nǀuu spectrum, or ǂKhomani (Doke 1937; Maingard 1937); or even from ‘ǃKung’ (ǃXun), which did not form part of the TUU (or ǃUi-Taa) languages at all.

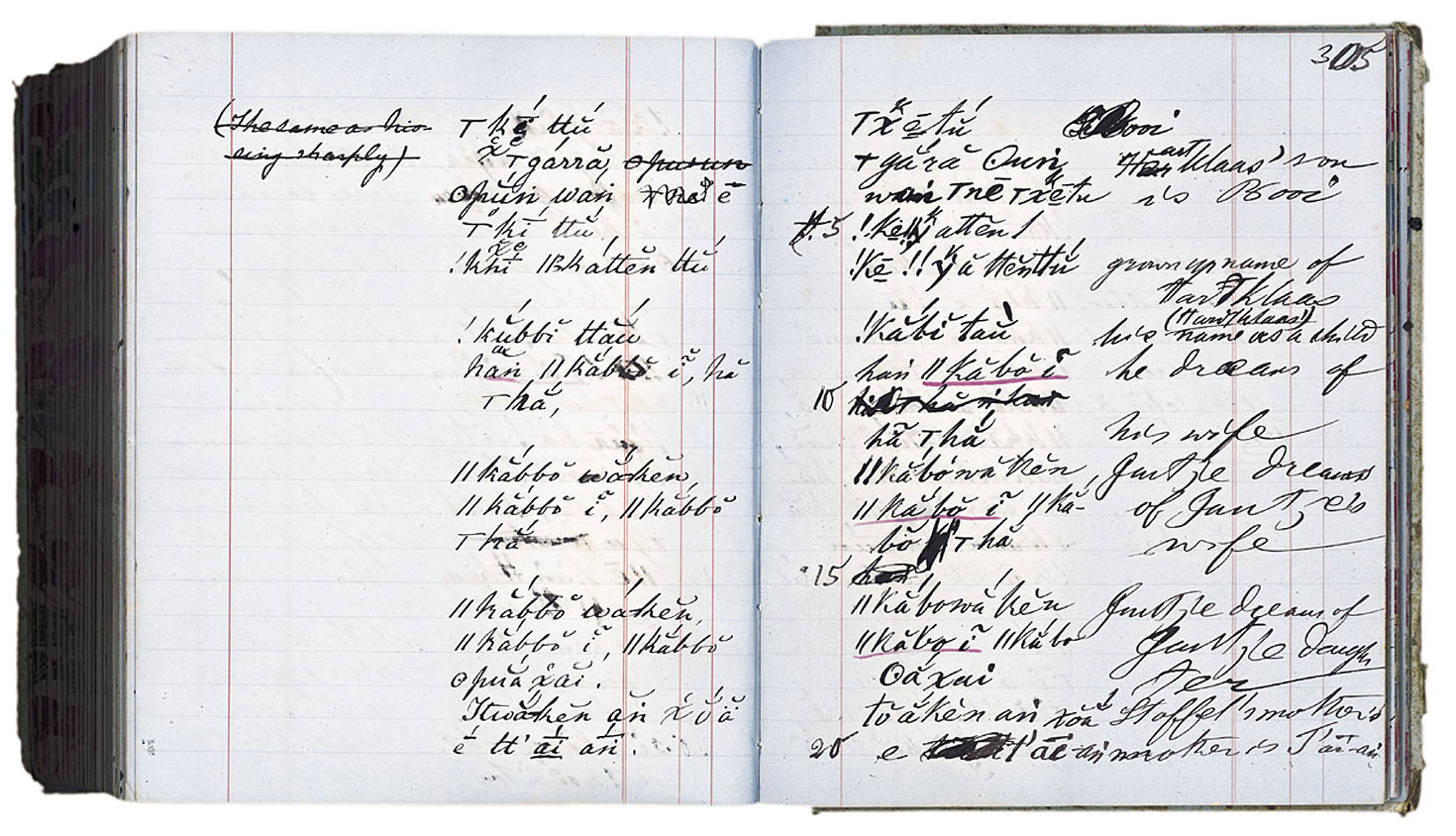

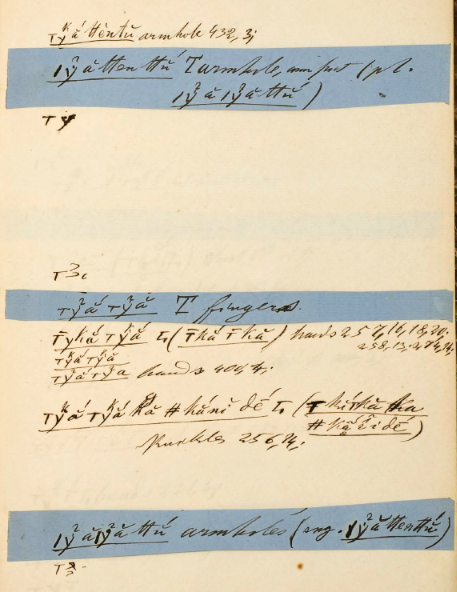

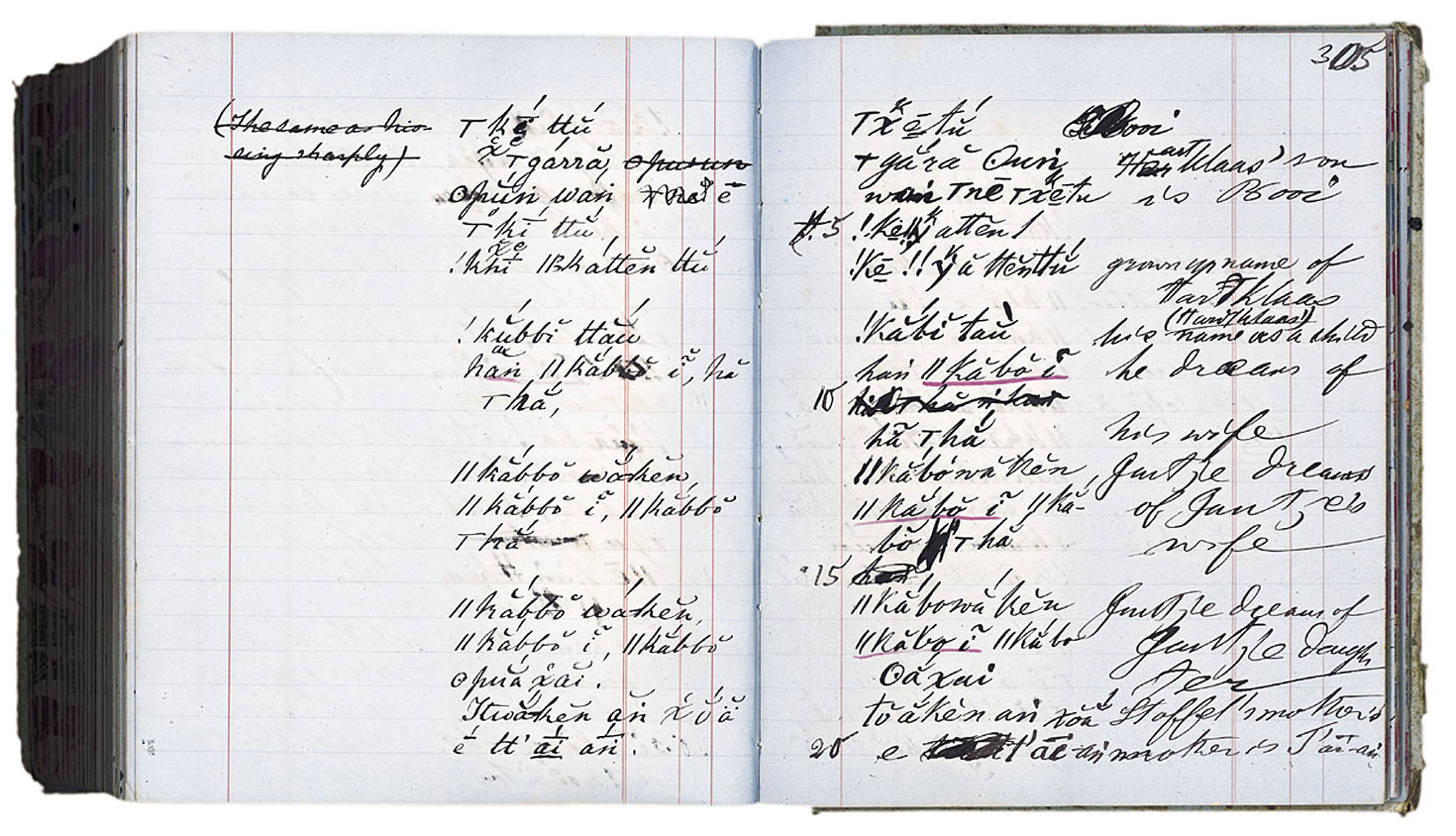

There are at least three – possibly four – different hands reflected in the manuscript entries. The handwriting of Wilhelm Bleek is generally unmistakeable, being characterised by increasing signs of his physical frailty, as well as evidence quite frequently of haste, perhaps induced by an awareness that he was in a race against time. In some cases, even quite early on in the project, Lloyd provided her own neat transcriptions on the page facing Bleek’s version (sometimes introducing different spellings of her own in the process.) In Bleek’s last few notebooks, there are several long stretches where Lloyd evidently took over the work of transcription from him entirely.

The writing on the right hand page, in Bleek’s first notebook (WB-ǁKab [1] 0305), is in his own hand, whereas the checked and neatly rewritten version on the facing page was supplied by Lloyd. It is notable that Lloyd spelled the borrowed word for ‘dream’ with a doubled consonant in the middle, as ǁkabbo, probably as a way of indicating the shortness of the first vowel. The spelling used by Bleek is more in line with the modern orthography for Namibian Khoekhoe, where the word is written as ǁhapos. (In Kora it is written as ǁhabos.)

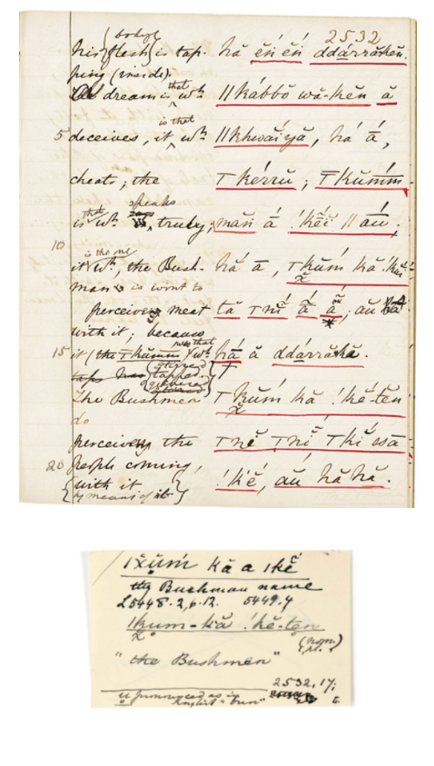

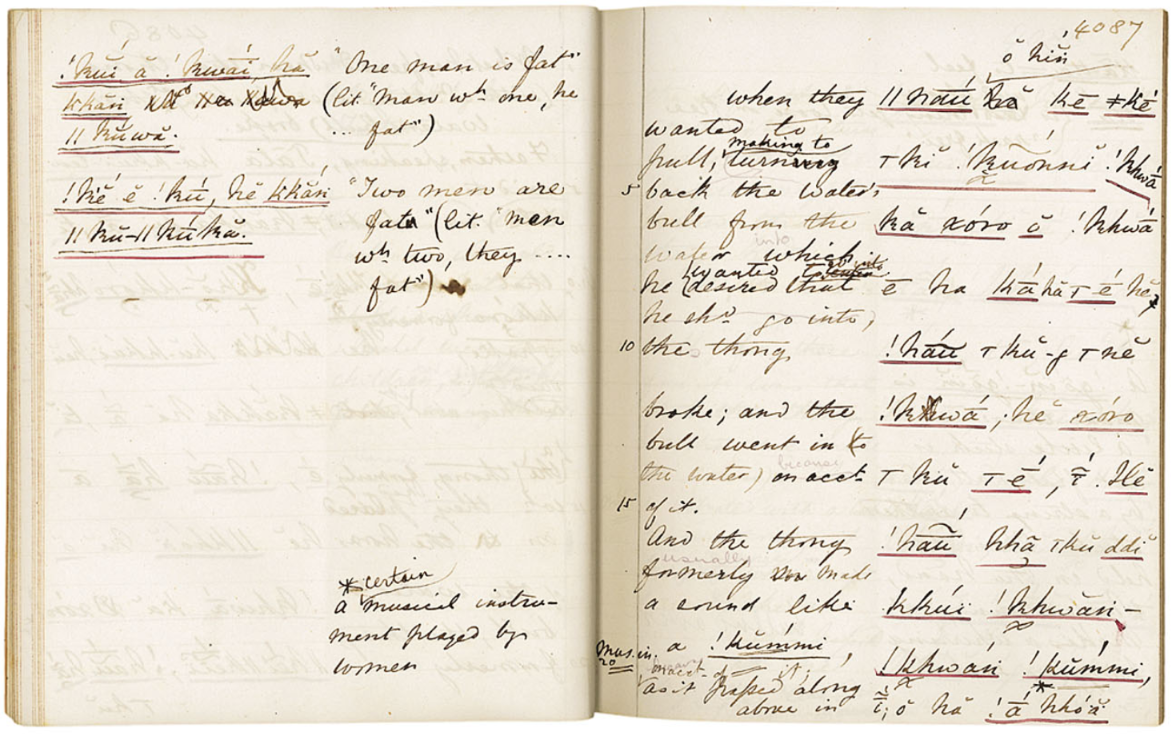

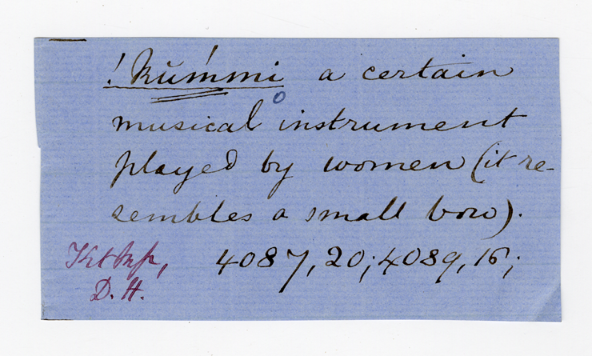

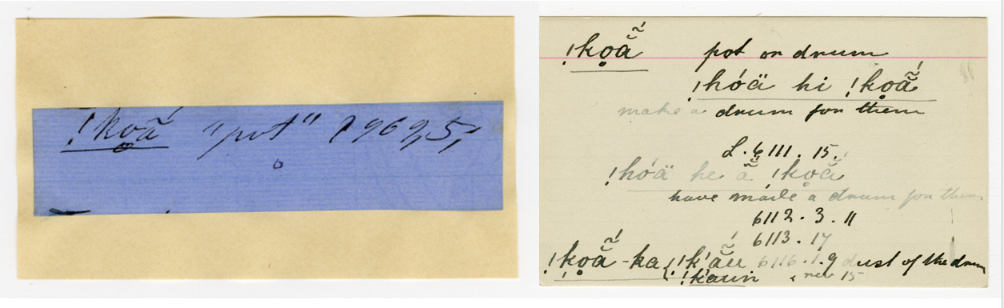

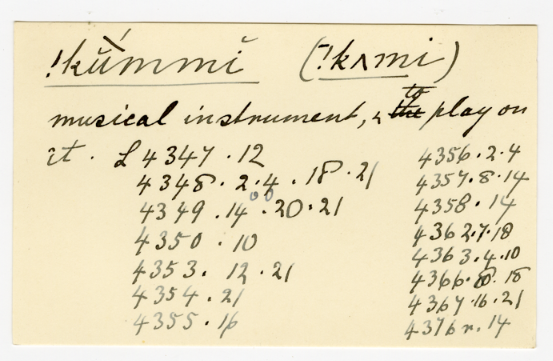

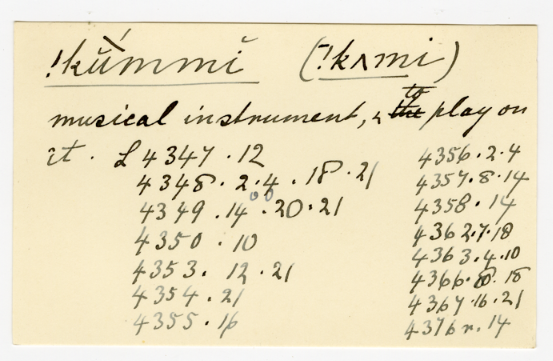

The slip above would seem to be in Dorothea Bleek’s hand, and includes a query in parentheses, where she has added a phonetic representation to clarify her aunt’s idiosyncratic spelling of the word ǃkami given by Dīaǃkwã̰in for a type of musical bow.

Background

Before briefly explaining the value of the slips, it will be useful to sketch the background to their compilation.

Wilhelm Bleek’s prior work on ǃUi languages, 1857 – 1869

The preparation of a comparative wordlist for Khoisan languages was clearly on Wilhelm Bleek’s research agenda from at least 1857, when he began compiling his manuscript ‘Vocabulary of the dialects of the [Khoi] and [San]’ for the use of his sponsor, the Cape Governor, George Grey. Bleek subsequently narrowed his focus to the varieties we know today as !Ui, and embarked on an early assembly of lexical items in his MS Bushman Vocabularies, volume 1 (1861-1867) and volume 2 (1870).

The first 65 pages in volume 1 of the Vocabularies constitute the Concordance drawn up by him on the basis of the vocabulary and example sentences for ǀNũsa sent to him by Georg Krönlein in 1861. ǀNũsa (or ǀNūsa) was a variety spoken north of the Gariep, and evidently formed part of the Nǀuu cluster. (A small amount of further data for this variety would be obtained at a much later date by Lucy Lloyd.) It is unfortunate that a printer’s gremlin introduced an incorrect spelling of ǀNũsa as ‘ǃNusa’ into an article published by Bleek in 1869, where he mentioned Krönlein’s contribution. This form subsequently found its way into a number of publications, both popular and academic, but it is entirely an artefact.

To round out his Concordance, Bleek incorporated additional early data from Lichtenstein (1812), as well as the brief sketch by Carl Wuras (ca. 1860). (It is striking that he omitted any mention of the words collected by Thomas Arbousset (1846), whose work he had certainly read. Perhaps this reflected the Franco-German enmity of the time.)

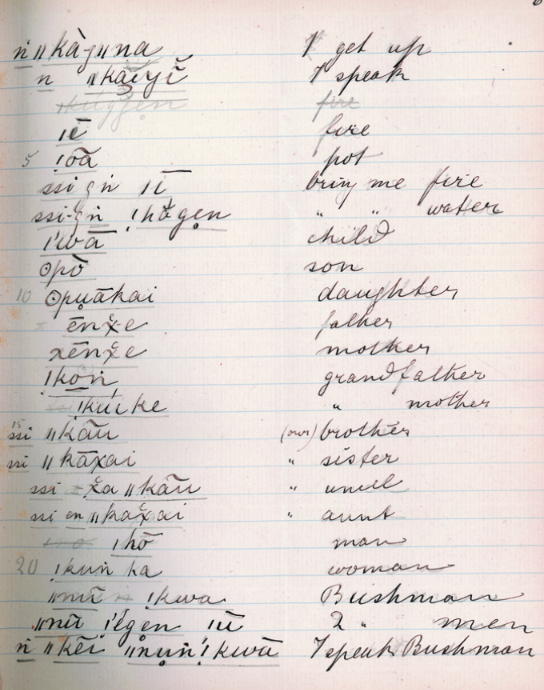

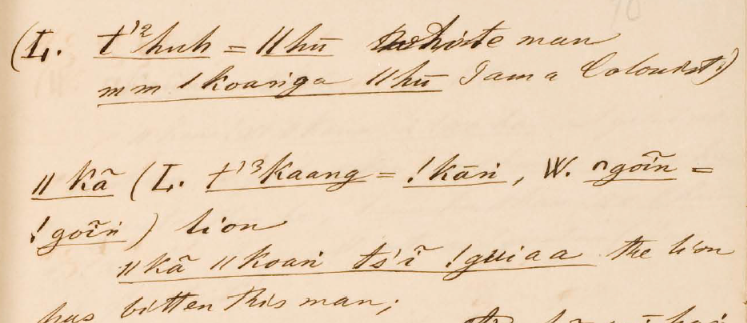

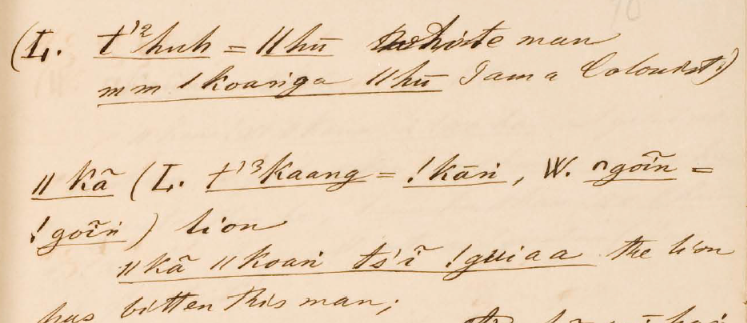

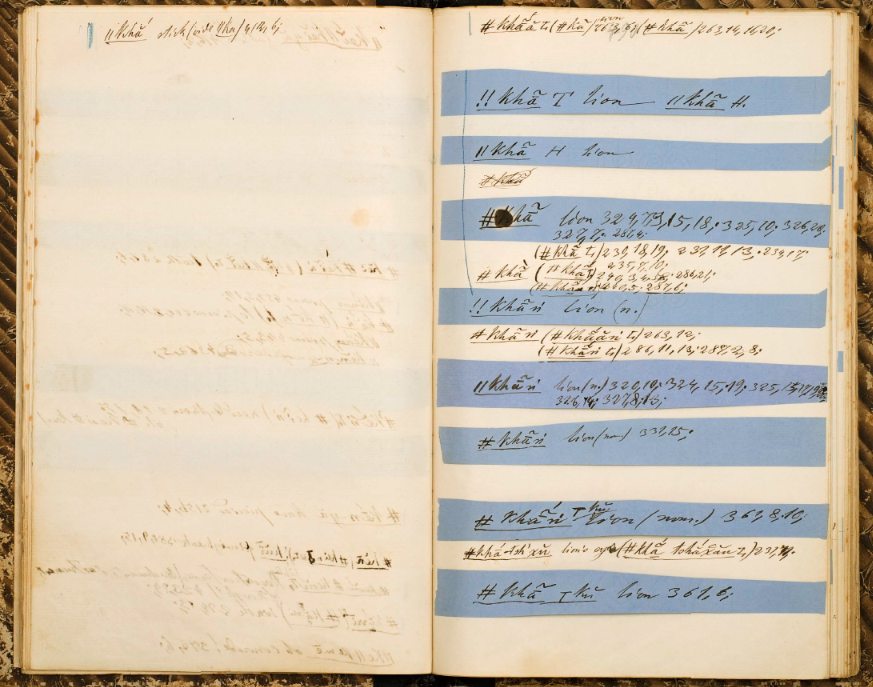

The page above is from Bleek’s Concordance for Krönlein’s ǀNũsa data in volume 1 of the MS Vocabularies. The items sourced from Lichtenstein (as in the case of the first item on the page shown here) are indicated by the same elaborate cursive capital L that Bleek would later use to indicate alternative transcriptions made by Lloyd. Items sourced from Wuras are indicated by a capital W, as seen here in connection with the words for ‘lion’.

The blue pages bound into the same volume include an early index of words accessed via their English translations, as well as a brief early list of ‘Bushman’ words. The latter were evidently those obtained by Bleek from Adam Kleinhardt in 1866. This speaker came from the Achterveldt, and the material provided by him was analysed and published by Bleek in 1869.

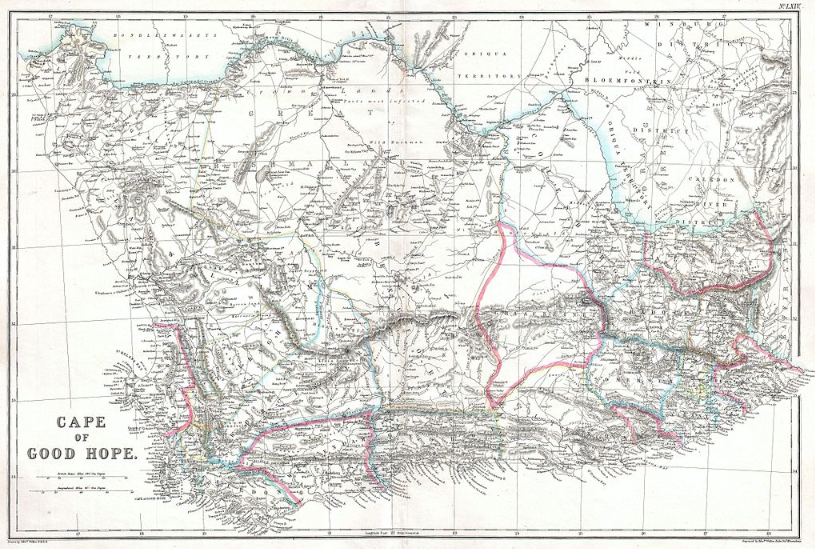

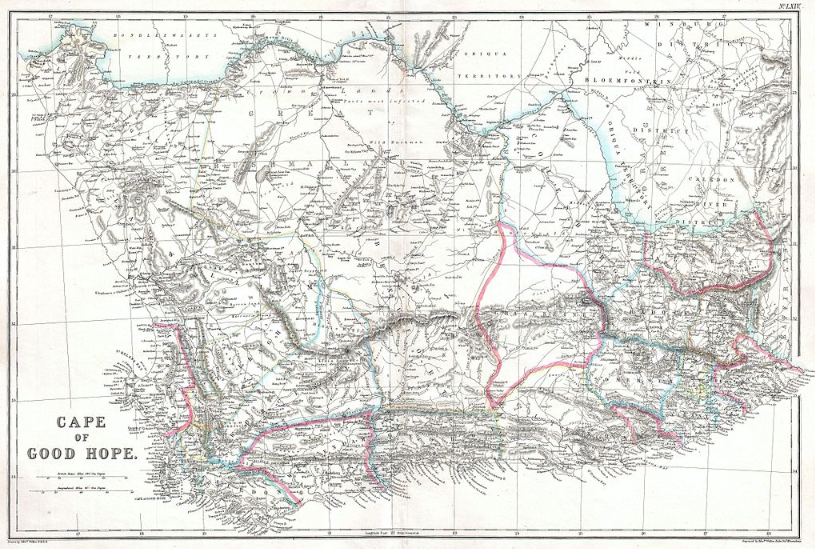

This map of The Cape of Good Hope from Blackie (1860) shows the location of the Achterveld, where Adam Kleinhardt came from, as well as the Winterveld, where Bleek surmised Lichtenstein had obtained his data. Bethany, where Wuras had an early mission station, is also shown, while the Maluti Mountains, where Qing lived, can be seen in the east. (Image from Geographicus Rare Antique Maps via Wikimedia, made available under a Creative Commons licence. Blue rings to mark specific places have been added.)

Pages 1–142 in volume 2 of the Vocabularies largely constitute a more extensive ‘English-Bushman Index’, although the first few pages were used for Bleek’s notes on the vocabulary of Qing sent to him by J. M. Orpen (published by the latter in 1874). We also find Bleek’s early attempts to classify the texts into the different categegories that he would use in his two Reports (1873, 1875), such as Poetry, Animals, Legends, Tales and Mythology; while the last few pages of the volume show Bleek’s working notes on the plural morphology of the nouns. The blue pages bound into this second volume also provide the beginnings of a more substantial ǀXam-English wordlist, with vocabulary obtained at first mainly from ǀAǃkungta, but later also ǁKabbo (who is indicated as the source by means of a capital letter T, presumably for ǁKabbo’s Colonial Dutch surname, Tooren or Toornar).

This first instantiation of a !Ui dictionary still reflects some of Bleek’s initial experiments with notation, and for this reason, among various others, was ultimately unsatisfactory. Bleek alluded to the work in his First Report on his research (1873, 6), with the follow-up comment that it was already in the process of being revised:

The further process of translation will be materially facilitated by the dictionaries in course of preparation. An English-Bushman Vocabulary of 142 pages, and a Bushman-English one of 600 pages folio contain the results of the earlier studies, which are now being greatly modifed and corrected by our better knowledge of the language.

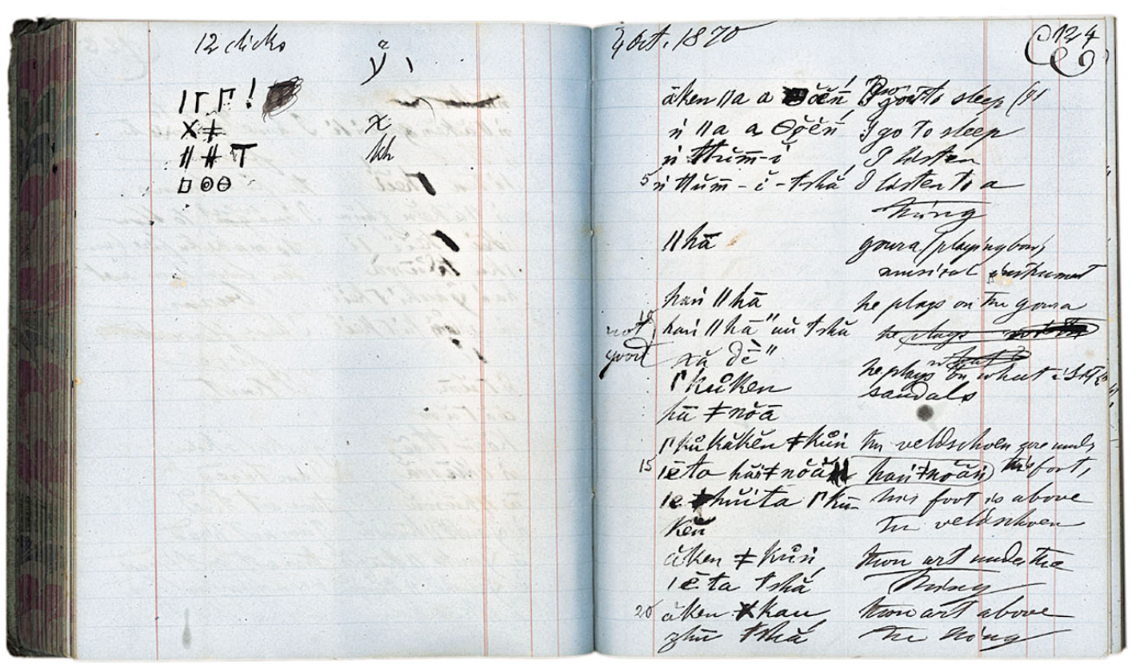

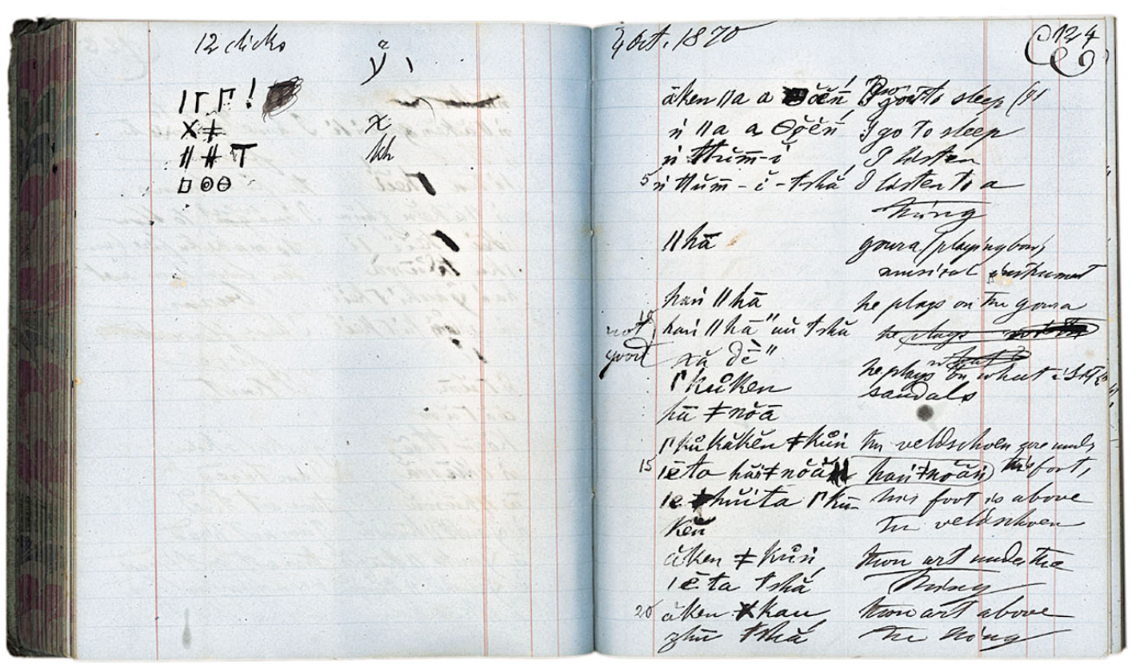

The notes on the page facing p. 124 in Bleek’s first

notebook indicate his identification of twelve click phonemes at this stage (October 1870) – and reflect his early experimental notations for them, using symbols drawn from Greek and Hebrew. His intention was evidently to provide a unique symbol for each click phoneme (which is to say, a given positional type of click – such as a dental or lateral – plus its elaboration by means of such features as voicing, aspiration or nasalisation, among others). Ultimately this proved unworkable, and he later reverted to a system of digraphs similar to the one already in use for Nama, with the addition of a few further letters to indicate click elaborations not found in that language.

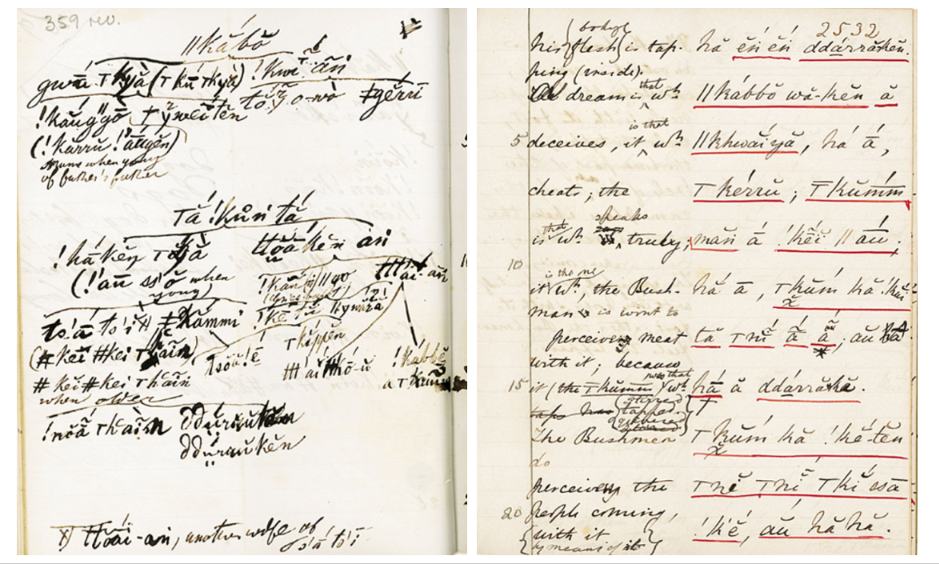

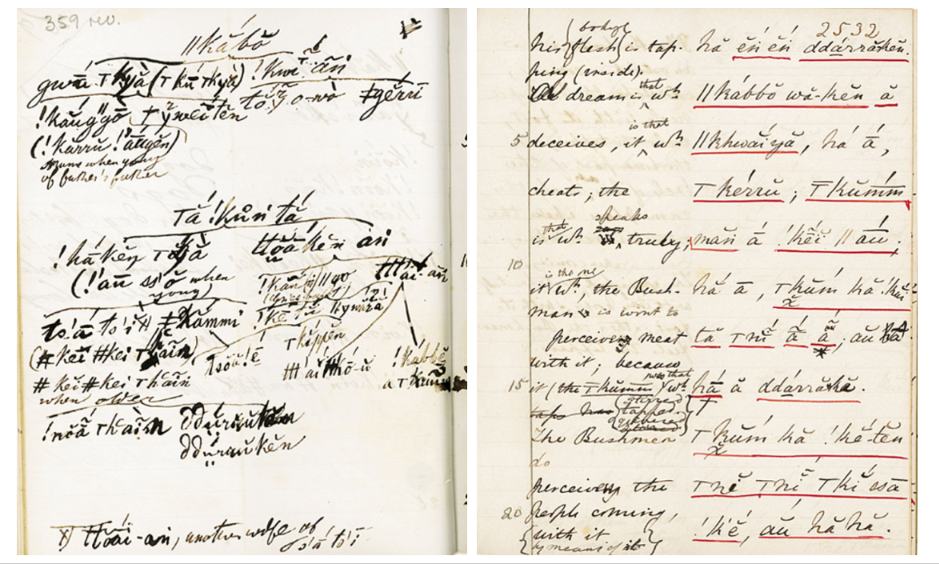

The page on the left above is from Bleek’s second

notebook , while the one on the right is from one of Lloyd’s early

notebooks. Both pages provide examples of Bleek’s experimental symbol for one of the lateral click phonemes, in the form of a double-barred double pipe (#). This symbol was later abandoned for the simple double pipe ǁ, with phonemically contrastive accompaniments indicated by the addition of letters such as ‘g’, ‘h’, ‘k’, ‘kh’, ‘n’, ‘x’ or ‘γ’. The ‘dotted n’ seen in the name ǀAǃkuṅta represented the velar nasal, or ‘engma’ /ŋ/. For the sake of legibility, it is best to replace ṅ with the digraph ng, as in the names, ǀAǃkungta, ǀHangǂkassō and ǂKāsing. Note also that the letter k written after a click symbol, as in ǁKabbo and ǂKāsing, indicates that the click is ‘plain’ (voiceless and unaspirated). Where a click symbol is written with no additional letter after it, as in ǀA, it is in fact ejected, and is characterised (like the clicks with ‘delayed aspiration’) by voiceless nasalisation before the click. (A similar convention is used for the ejected clicks of Namibian Khoekhoe.

The period of Bleek and Lloyd’s collaboration, 1870 – 1875

Bleek’s next attempt to deliver a ǃUi dictionary dates from the beginning of his collaboration with his sister-in-law, Lucy Lloyd, and consists of a Bushman Dictionary in four MS volumes (all 1871). There is no English look-up side provided for this version, but it was probably the intention to revise and expand the draft already begun in volume 2 of the Vocabularies (1870). Here the notation begins to stabilize, and there is a growing coherence reflected in the organisation of the entries.

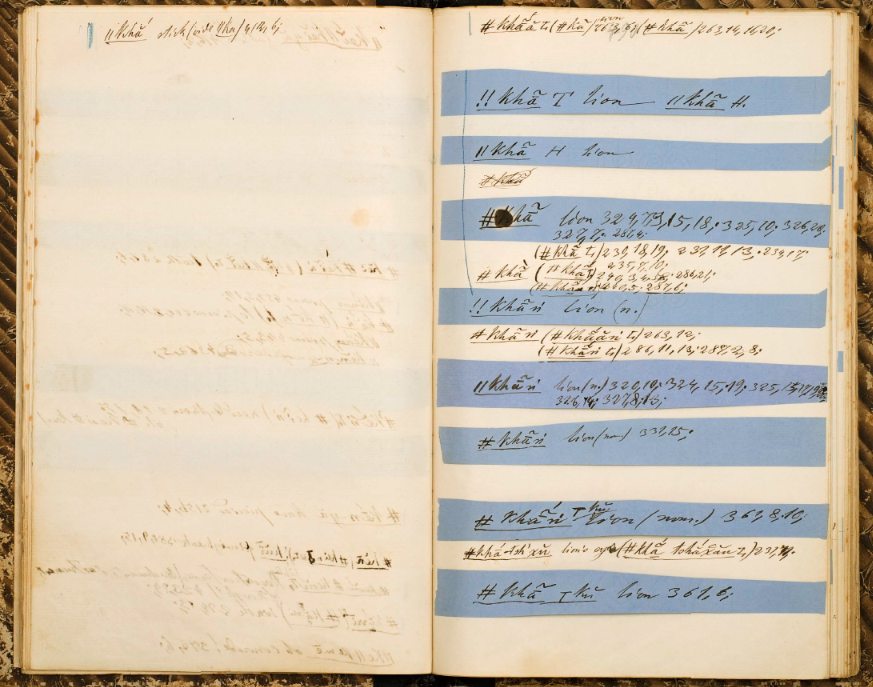

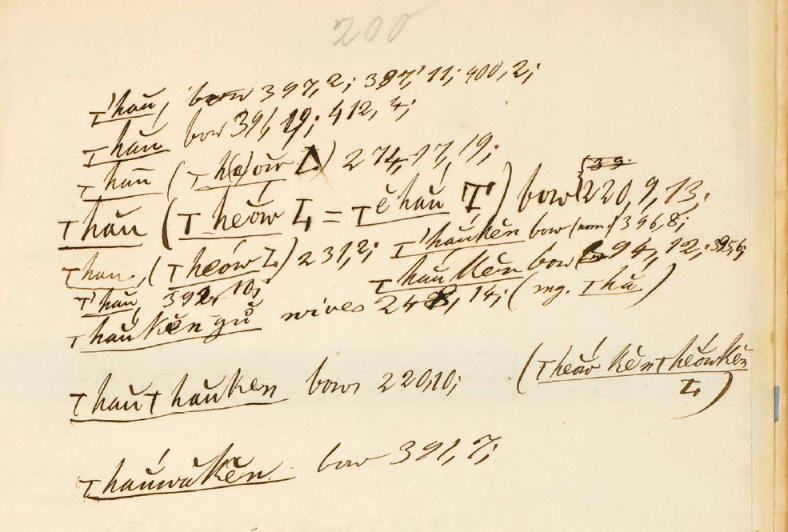

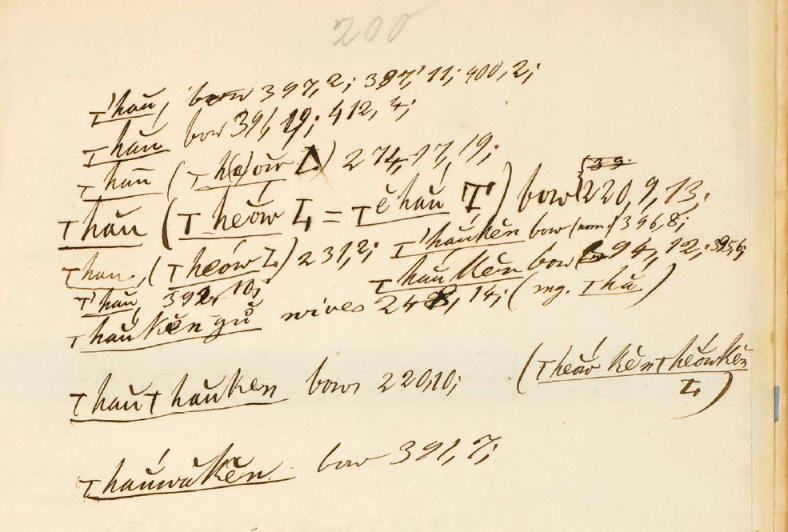

This page from volume IV of the MS Dictionary shows the use of the initials T and H to distinguish the contributions of ǁKabbo (Jantjie Tooren) and Dīaǃkwã̰in (Dawid Hoesaar). The older experimental notations used by Bleek to distinguish individual click phonemes are now grouped together, as seen here, where the symbols ‼, ǁ and # for various phonemic forms of the lateral click are treated as part of the same sequence.

A few entries begin to appear in the Dictionary marked with the letter H for Dīaǃkwã̰in (Dawid Hoesaar), indicating a gradual inclusion of Katkop lexis from 1873 onwards. Lastly, any alternative transcriptions by Lloyd are now regularly indicated by a capital letter L.

This page from volume II of the MS Dictionary shows the use of Lloyd’s monogram to indicate her alternative transcription of the word for ‘bow’. Bleek and Lloyd did not consistently distinguish between ao and au (both of which can also occur with nasalisation), although we can deduce that a diphthong must have been au /əʊ/ in cases where Lloyd recorded a variant spelled as ou or (e)ou – as in the fourth version of the word for ‘bow’ seen here. Similarly, they did not always distinguish between ae and ai (both of which can likewise occur with nasalisation), although it is clear that the diphthong must have been ai /əɩ/ in cases where variant spellings are given as ei, as in the name of ǂKāsing’s wife, ǃKweiten-ta-ǁkēng. The example above also illustrates Lloyd’s habit of recording a brief and unstressed vowel that appears to intervene between a click and the accompaniment of ‘delayed aspiration’. In reality, the perception of such a sound is mistaken, and the word for ‘bow’ should be written simply as ǀhau.

A third version of a dictionary was evidently in the process of being prepared at the time of Bleek’s sadly early death in August 1875, as we have already seen mentioned in Jemima Bleek’s letter to George Grey. Lloyd similarly noted, in the belatedly published Third Report (1889: 5), that:

Dr Bleek had also made much progress in dividing and sorting the entries for his Bushman-English Dictionary; upon which sorting he was engaged during the last weeks of his life, and had, on the last night, nearly completed.

This work of ‘dividing and sorting the entries’ is what gave rise to the collection of slips in the shoeboxes.

Lucy Lloyd’s continuation and broadening of the work, 1875 – 1889

At the time of Wilhelm Bleek’s death, the Katkop speaker, Dīaǃkwã̰in, was still with the Bleek household. As Lloyd explained in the Third Report (1889: 3), he remained on to assist her with the research until March 1876. In April 1877, ǀHangǂkassō (the son-in-law of ǁKabbo) finally arrived in Mowbray after protracted efforts to locate him. He worked with Lloyd until December 1879.

Between April and August 1880, Lloyd evidently had the opportunity to interview a few more speakers at the Breakwater Gaol. One of these, ǀXabeten (also known as Mkuan), spoke an eastern variety of !Ui, and additionally spoke Phuthi(LL-ǀXabe [123]). In this respect he was much like the unknown speakers interviewed by Arbousset in the vicinity of the Maluti Mountains, as well as the speaker known as Qing who assisted Orpen, and who came from the same region.

In September 1880, Lloyd was able to work with another speaker, ǃNauxa (or Petrus Willem). She took him on a visit to the Museum, where she elicited the names of various animals from him. He was said to be a ‘Grass Bushman’ (one of the ǀKhe ǁeng or ‘Grass people’, who were also known as ǀNusa ǃke), and explained that he lived ‘in the “Sand Duine”, the veldt, far on the other (i.e. the further) side of the Orange River’. His variety fell within the Nǀuu spectrum, much like that of the Katkop speakers, who were similarly referred to by the Swa-ka ǃke (the ‘Flat’ or ‘Plains people’) as ǀNusa ǃke.

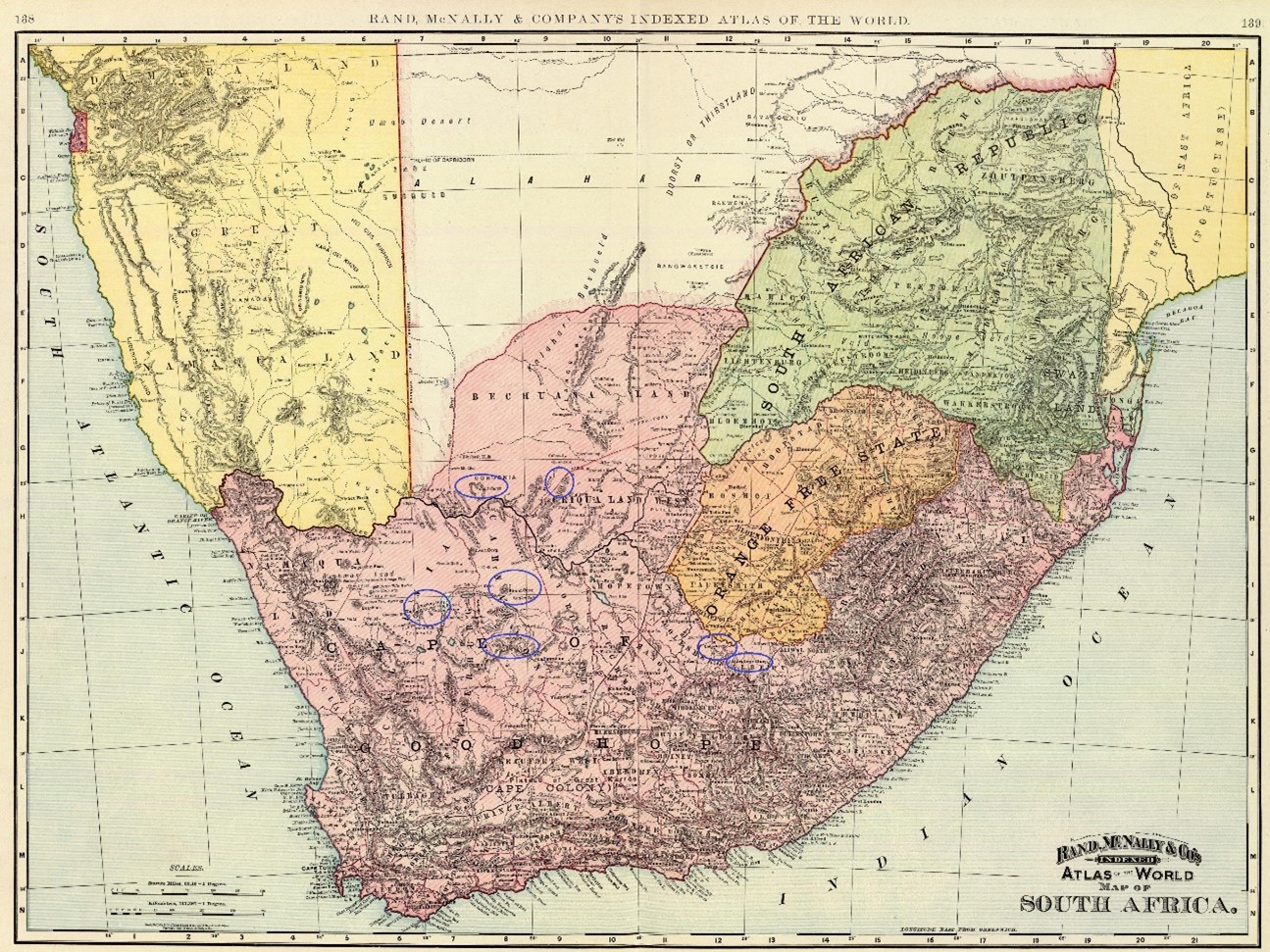

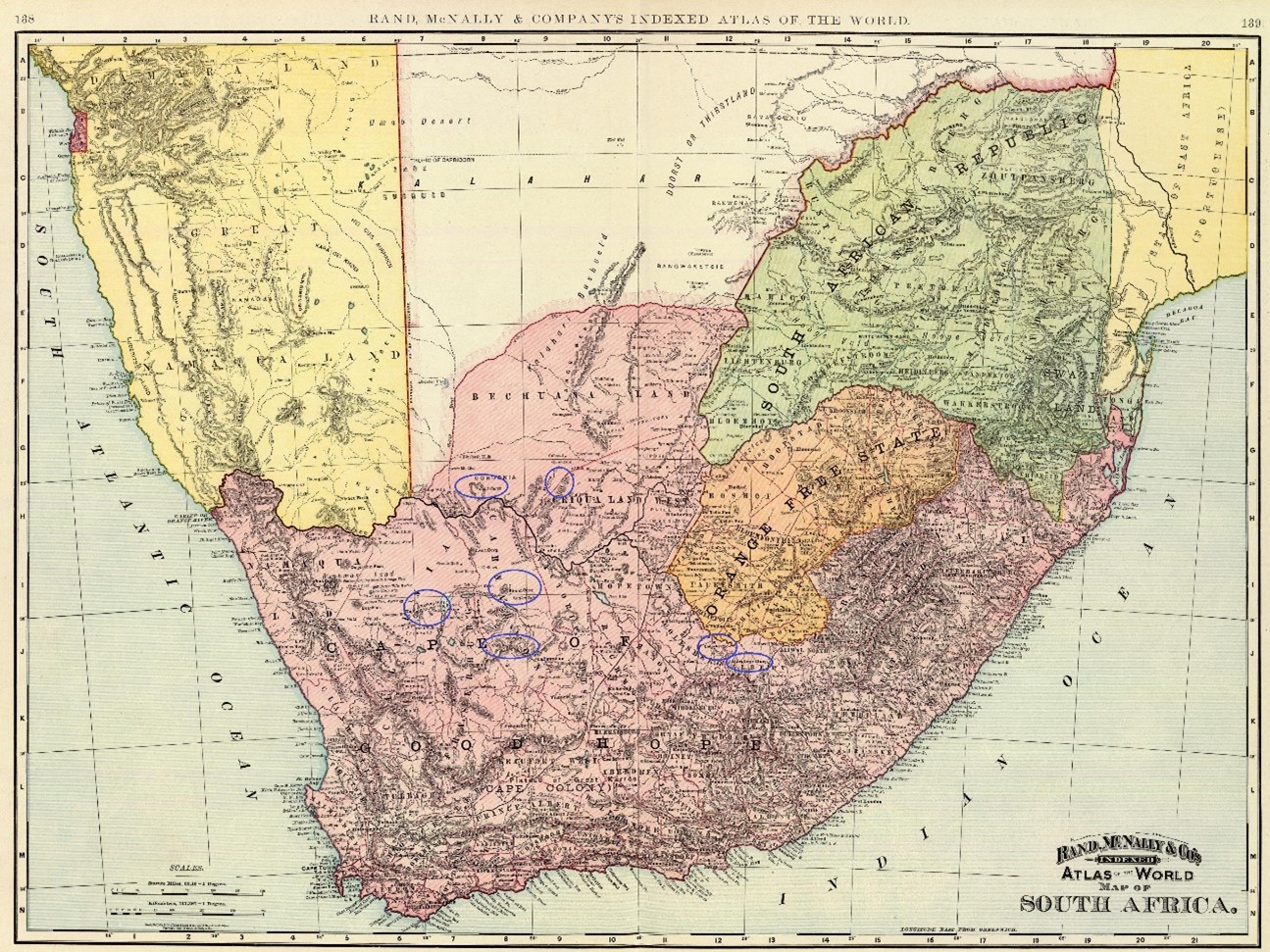

The Rand-McNally map of South Africa (1892) indicates a region known as the Sand Dunes (Sand Duine) just north of the Gariep, in Gordonia. There are several mountain ranges named Langeberg in South Africa, but the region referred to by Lloyd and later visited by Dorothea Bleek was the one seen here within the territory then known as Griqualand West. Other places circled on the map are the Strontberg, the Katkop Hills, the Kareebergen, Colesberg and Burghersdorp. (Image from the David Rumsey Map Collection (Cartography Associates), made available under a Creative Commons licence. Blue rings to mark specific places have been added.)

At some point between 1880 and 1889, Lloyd had a further opportunity to interview speakers at the Breakwater, two of whom were said to be ‘of ǀNusa extraction’. A third speaker, known as Xumǀna, came from the vicinity of the Langeberg. The notebook containing the records of the interviews with these three speakers is unfortunately missing, but seems likely to have been slender. Lastly, in March 1884, Lloyd obtained a small amount of information from a speaker known as ǀXaken-ang (or Mikki Streep). This notebook is also missing, but it was probably equally slender.

Lloyd worked with speakers of various other languages, including Nama, Kora and ǃXun – but since these belong to entirely different families, they are not relevant here.

Dorothea Bleek’s contribution, c. 1910–1948.

During her initial apprenticeship to her aunt, Dorothea Bleek seems to have been charged fairly early on with the checking and continued organisation of the dictionary slips in the shoeboxes. She made many additions to them, noting further tokens of a given word found in the notebooks, and providing additional page references. It’s clear from her method of filing that she was grouping together some of Bleek and Lloyd’s variant spellings, following in the footsteps of her father, who had already begun to rationalise some of these, as we have seen.

Despite the attempts at a more coherent ordering, the slips in the shoeboxes are in several respects still chaotically organised, partly because of the numerous variations in the representation of a given word by Bleek and Lloyd, and partly because a series of words beginning with a particular click phoneme is often interrupted by others, even though they should be filed as a single complete sequence. (The series of ejected clicks, which are represented by the click symbol without any following letter, are typically interrupted after the words with e as their second letter – in order to bring in words beginning with voiced and aspirated clicks, since these are represented respectively by the letters g and h after the click symbol. The series of ejected clicks resumes with words that have i as their second letter – only to be interrupted again by the plain clicks, which are indicated by the addition of the letter k. After a further intrusion of words beginning with nasalised clicks, where the nasalisation is shown by addition of the letter n, the original series of ejected clicks picks up again with words that have o as their second letter.)

In addition, the plain clicks are sometimes treated for filing purposes as interchangeable with the clicks accompanied by a fricated uvular ejective – when represented by the click symbol plus k’ – although when these clicks are written with the alternative Greek small letter gamma (γ), they are then typically placed at the end of a series. The clicks with simple frication (indicated by addition of the letter x) and the aspirated or fricated uvular (indicated by addition of kh) are often similarly treated as interchangeable, and words commencing with them will sometimes be found in one place, and sometimes in another.

When she was ready to begin conducting research of her own, Dorothea Bleek took the admirable step of travelling considerable distances across South Africa, to the remote areas where speakers were still to be found. As we have already seen, her earliest field research was conducted in the vicinity of the Langeberg, and along the course of the Gariep, where she interviewed several speakers whose varieties of ǃUi belonged mainly to the Nǀuu spectrum. (She later worked with speakers of several other languages, including the ǀ’Auo language spoken by the ǀ’Auni, and ǃXoon, both of which belong to the Taa branch of TUU; as well as Naro; and varieties of ǃXun.)

Dorothea Bleek published an account of the click phoneme inventory of ǀXam (1923), and also offered an early outline of the grammar (1928/28 and 1929/30), in which she incorporated most of the insights of her father and aunt, as well as some suggestions of her own. Ultimately, though, she bypassed the work of making a dedicated dictionary for ǀXam, and instead laboured on to add more and more data for other languages – perhaps out of a desire to complete her father’s unfinished early project of assembling a comparative database. This accumulated material enabled her to to publish a set of Comparative Vocabularies in 1929. The work presented selected lexis from seven of her ‘Southern’ languages (four ǃUi and three Taa); three closely related varieties of ǃXun, from the languages she identified as ‘Northern’; and two varieties from her ‘Central’ group – with Nama items included for comparison, and with English as the look-up language.

Finally, Dorothea Bleek’s Bushman Dictionary, published posthumously in 1956 – just one year short of a century after her father began his work on ǃUi – was a compendium of lexis drawn from 28 languages, where these not only belonged to three entirely different families, but even additionally included the Tanzanian isolate, Hadza, which she had herself documented in 1930. The ǃUi languages are represented by the various entries labelled SI and SIa, SIIa–e, SIII, and SVI and SVIa – where the ‘S’ stands for Southern. As for ǀXam itself, the two dialects of Strontberg and Katkop are not distinguished but are jointly numbered SI, and are moreover lumped together with the variety briefly documented by Lichtenstein.

While it has a cherished place in many researchers’ libraries, Dorothea Bleek’s Bushman Dictionary is not an easy resource to use. Apart from its bewildering inclusion of data for multiple, unrelated languages, the sequencing of entries follows the same erratic system used to file the slips in the shoeboxes, where what should be a single series is typically interrupted at several points. The Dictionary has a brief index at the end, which might have served as an abbreviated English look-up side, except that the corresponding words from the various unrelated families are simply listed in long strings, without any identification of the source languages.

In short, we are left today still very much in want of a dedicated ǀXam-English, English-ǀXam dictionary.

The value of the slips

As the background sketch will have made clear, the slips in the shoeboxes were intended by Bleek and Lloyd to form the basis of a third, finally revised ǀXam-English, English-ǀXam dictionary. This vision was never realised, but even though the slips in themselves do not constitute a practical dictionary – they nevertheless form an immensely valuable collection of the primary data needed for the completion of the original project.

A properly functional modern dictionary for ǀXam will be based on an appropriately standardised citation form for each lexical entry, with additional information concerning various relevant aspects of morphology. The following questions are among those needing to be resolved:

- (1) What was the phoneme inventory of ǀXam?

- (2) What were the grammatical morphemes used in ǀXam, including: noun and verb suffixes; particles used in the expression of tense, aspect and modality as well as polar and constituent questions; and particles associated with the marking of information structure?

- (3) How many grammatical genders were reflected in ǀXam, and what agreement morphology was used to express them?

- (4) How many true adjectives –as opposed to relative stems– were used in ǀXam, and how were these incorporated into the noun phrase?

- (5) What relational nouns were used to express locative implications in ǀXam, and what syntactic patterns were involved in their use?

- (6) What ‘deficient verbs’ (or ‘idiomatic verbs’) were used as auxiliaries in ǀXam: and what implications of tense, aspect or modality did they express?

- (7) What strategies were involved in the compounding of nouns and verbs, and to what extent were these productive?

- (8) What examples from the texts can be provided to illustrate use?

- (9) What are the different varieties reflected in the Bleek and Lloyd records?

- (10) Which words were borrowed, and from what languages did they come?

When we turn to the slips, we find preliminary answers to many of these questions already provided for us in the tentative comments left by Bleek and Lloyd. Page references to the texts are provided in scrupulous detail – almost all of them carefully checked by Dorothea Bleek. Wilhelm Bleek understood the importance of distinguishing the Katkop dialect from Strontberg, and always labelled entries as Katkop where applicable.

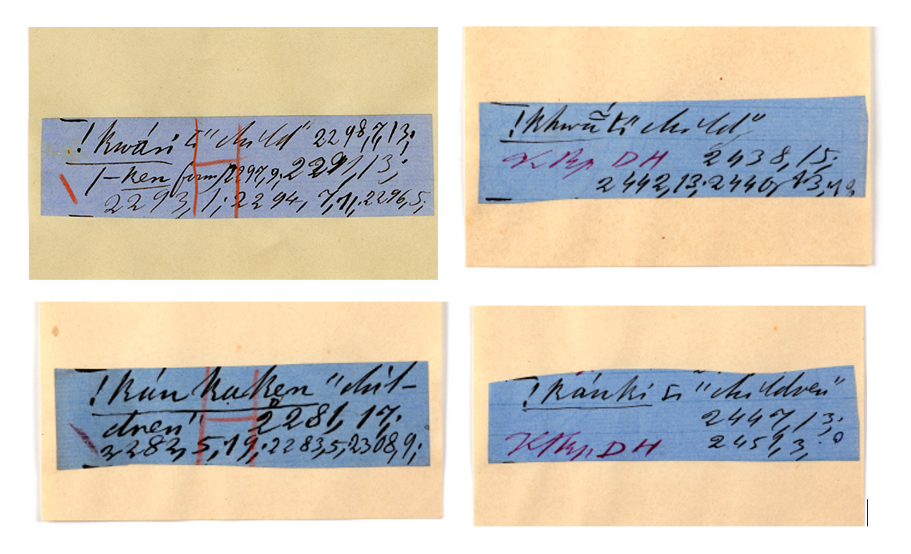

The slips at the top above show the singular form of the word for ‘child’ in the Strontberg dialect of ǁKabbo (left), and in the Katkop dialect of Dīaǃkwã̰in (Dawid Hoesaar). The two slips below them show the plural forms in the two dialects respectively. The formation of a plural by means of the suffix -ki is one of the features that suggest the affinity of Katkop with the Nǀuu spectrum.

Bleek also identified some of the numerous borrowings from Khoekhoe sources that characterise all ǃUi languages, having access at this time to vocabularies for Nama from the Grammar and Vocabulary of Henry Tindall (1858) as well as his personal correspondence with Krönlein, and also for Kora (Wuras 1858). Plural forms are noted; and grammatical genders are indicated, where they had been determined. The slips even include notes (albeit sometimes mildly cryptic) on the function of various grammatical morphemes.

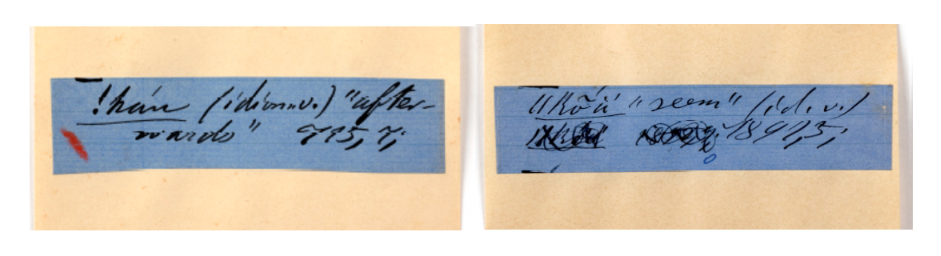

We know from comments made by Bleek (1858: 46) in his Catalogue of the Library of George Grey that he greatly admired John Appleyard’s Grammar of the [Xhosa] language (1850). So, when we come across abbrevations such as “id.v” or “idiom.v.”, as seen here, we know that he was identifying these verbs as belonging to a similar class of auxiliaries as those termed ‘idiomatic verbs’ by Appleyard. (They were given the name ‘deficient verbs’ by Clement Doke in 1935.)

Conclusion

For all their inevitable shortcomings, the slips in the shoeboxes remain a primary resource of inestimable value, and their digitisation is a fitting homage to the scholarly processes of both Bleek and Lloyd - endlessly revelatory of the ways in which their understanding developed and deepened over time.

Short Bibliography

Many of the works listed below are freely available online from the Internet Archive, while some can be found on Google Books.

- Appleyard, John. 1850. The [Xhosa] language. King William’s Town: Wesleyan Missionary Society.

- Arbousset, Thomas and Francois Daumas. 1846. Narrative of an Exploratory Tour to the North-East of the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope, transl. John Croumbie Brown. Cape Town: A.S. Robertson, Saul Solomon and Co.

- Bank, Andrew. 2006. Bushmen in a Victorian World. Cape Town: Double Storey Books.

- Bleek, Dorothea F. 1910–1936. MS notebooks documenting ǃUi varieties as well as various other Khoisan languages, and also the Tanzanian isolate, Hadza. Housed in the Bleek Collection (BC 151), Manuscripts and Archives, in the Special Collections of the University of Cape Town Libraries. Available online at http://lloydbleekcollection.cs.uct.ac.za.

- —1923. “Note on Bushman orthography.” Bantu Studies 2: 71–74.

- —1927. “The distribution of Bushman languages in South Africa.” In Festschrift Meinhof (Hamburg: Augustin), 55–64.

- —1928/29. “Bushman Grammar.” Zeitschrift für Eingeborenen-Sprachen 19: 81–98.

- —1929. Comparative Vocabularies of Bushman Languages. Cambridge: University Press.

- —1929/30. “Bushman Grammar (contd).” Zeitschrift für Eingeborenen-Sprachen 20: 161–174.

- —1956. A Bushman Dictionary. New Haven, Connecticut: American Oriental Society.

- Bleek, Wilhelm H. I. 1857. A Vocabulary of the Dialects of the [Khoi] and [San]. MS notebook housed in the George Grey Collection, South African National Library, Cape Town.

- —1858. The Library of His Excellency, Sir George Grey: Philology. London: Trübner and Co.

- —1861–1870. MS Bushman Vocabularies (vols 1–2). MS notebooks, housed in the Bleek Collection (BC 151), Manuscripts and Archives, in the Special Collections of the University of Cape Town Libraries.

- —1862. Concordance: analysis of Nǀũsa data sent by the Rev. Georg Krönlein in 1861. MS, in Bushman Vocabularies, vol. 1.

- —1869. “The Bushman language.” In The Cape and its People, ed. Roderick Noble (Cape Town: Juta), 269–284.

- —1871. MS Bushman Dictionary (vols I–IV). MS notebooks, housed in the Bleek Collection (BC 151), Manuscripts and Archives, in the Special Collections of the University of Cape Town Libraries.

- —1873. “[First] Report of Dr Bleek concerning his researches into the Bushman language and customs.” Cape Town: Printed by Order of the House of Assembly.

- —1875. “Dr Bleek’s Second Report concerning Bushman researches, with a short account of the Bushman native literature collected.” Cape Town: Saul Solomon.

- —1911. “‘The Resurrection of the Ostrich’: part of the preceding tale parsed by Dr Bleek.” In Specimens of Bushman Folklore, ed. and comp. W. Bleek and L. Lloyd (London: George Allen), 144–154.

- Bleek, Wilhelm and Lucy Lloyd. 1870–1875. MS notebooks documenting ǀXam and other ǃUi varieties. Housed in the Bleek Collection (BC 151), Manuscripts and Archives, in the Special Collections of the University of Cape Town Libraries. Available online at http://lloydbleekcollection.cs.uct.ac.za.

- —1911. Specimens of Bushman Folklore. London: George Allen.

- Bleek, Wilhelm, Lucy Lloyd (and Dorothea Bleek). 1870–(1928 [?]). Collection of notecards towards a revised ǀXam–English Dictionary. MS slips in shoeboxes, housed in the Bleek Collection (BC 151), Manuscripts and Archives, in the Special Collections of the University of Cape Town Libraries.

- Doke, Clement M. 1935. Bantu Linguistic terminology. Cape Town, London: Longmans, Green and Co.

- —1937. “An outline of ǂKhomani Bushman phonetics.” In Bushmen of the Southern Kalahari, ed. J.D. Rheinallt Jones and C. M. Doke (Johannesburg: Wits University Press), 61–88.

- Güldemann, Tom. 2004. “Studies in Tuu (Southern Khoisan).” Leipzig: Institute for African Studies, Leipzig University.

- Krönlein, J. G. Manuscript letters to Wilhelm Bleek [ca. 1861–1862]. Housed in the George Grey Collection of the South African National Library, Cape Town.

- Lichtenstein, Henry. 1812. Travels in Southern Africa in the Years 1803, 1804, 1805, and 1806 (2 vols), transl. Anne Plumptre. London: Henry Colburn.

- Maps:

- Blackie. 1860. Map of the Cape of Good Hope. From The Imperial Atlas of Modern Geography. Glasgow: W. G. Blackie and Sons.

- Rand McNally. 1892. Map of South Africa. From Indexed Atlas of the World (1897). Chicago: Rand McNally.