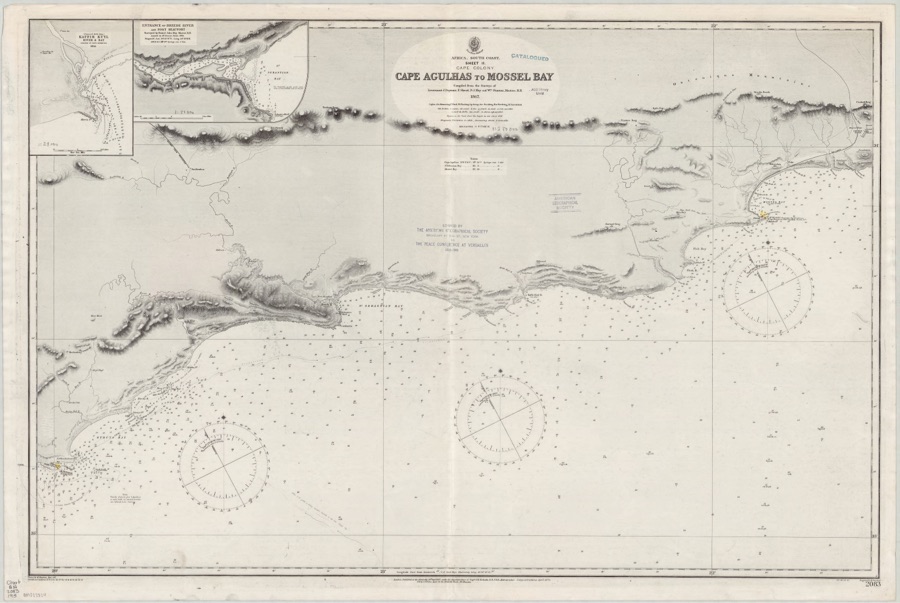

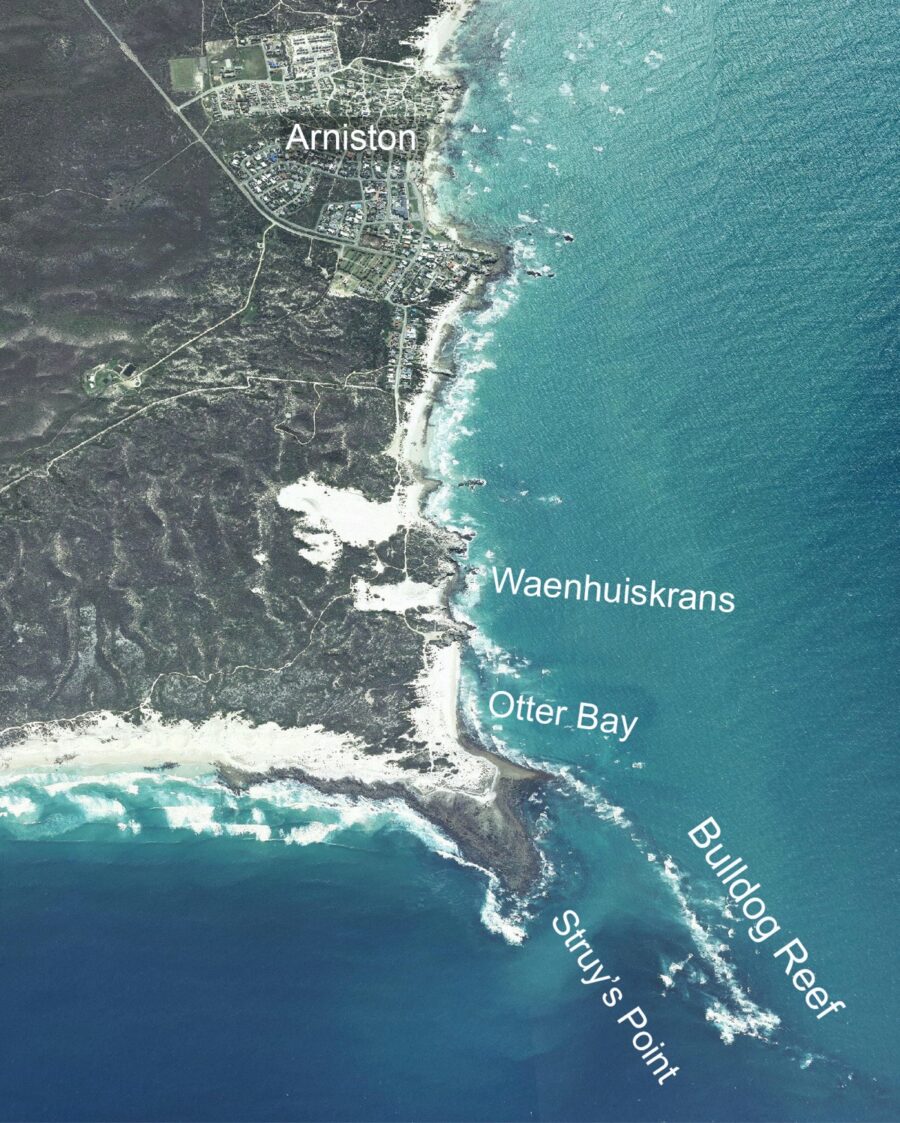

Sixteen women were on board the ship and they were the first to be rowed to shore and safety. One of these, listed in the Saloon class, was Lucy Catherine Lloyd, travelling from Natal to the Cape where she was to assist her sister Jemima’s fiancé, Wilhelm Bleek, with preparations for their wedding. Her loving letter to her sisters written just after the wreck hints at the drama of the night and the enormous relief that all on board were rescued. We are all alive – & safe & well, she wrote. The steamer ran ashore near Struys bay I think they call it – but we are all safe – & I never can feel grateful enough that all the dear precious lives were spared …2

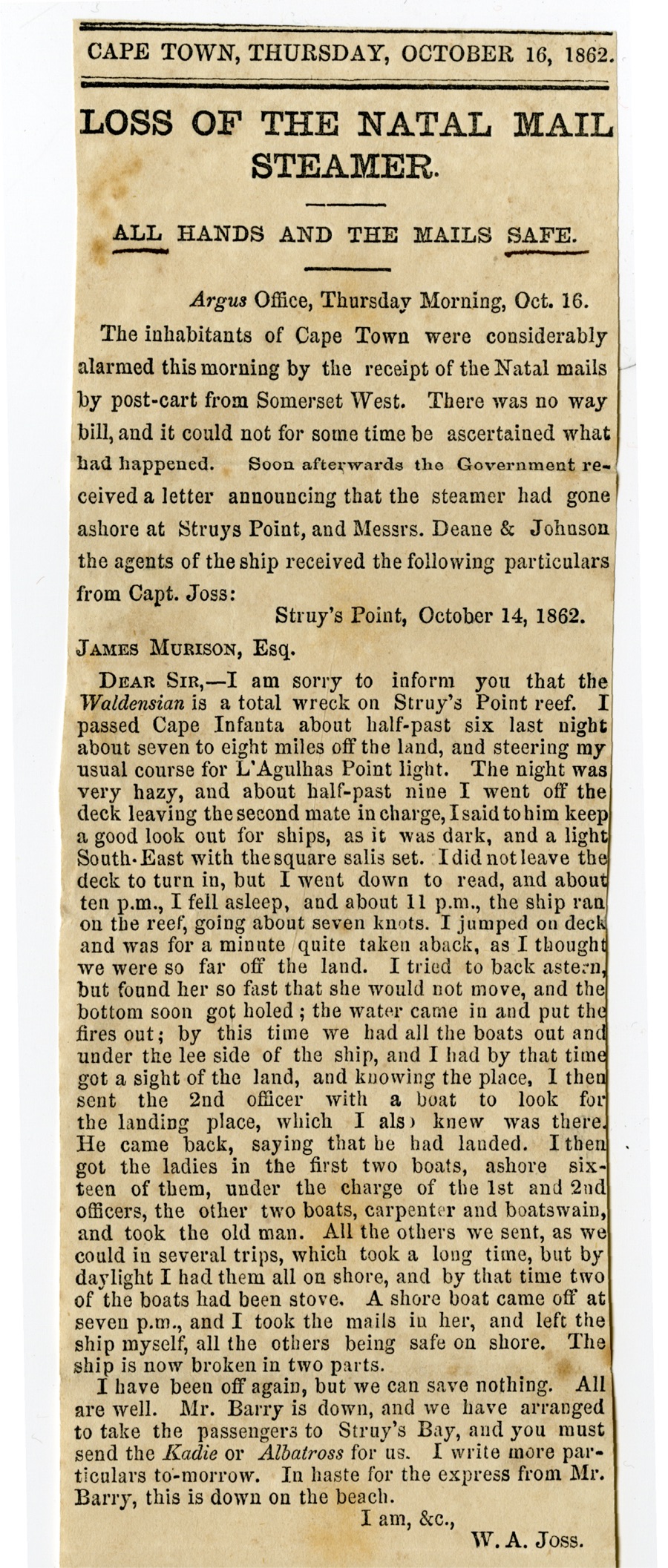

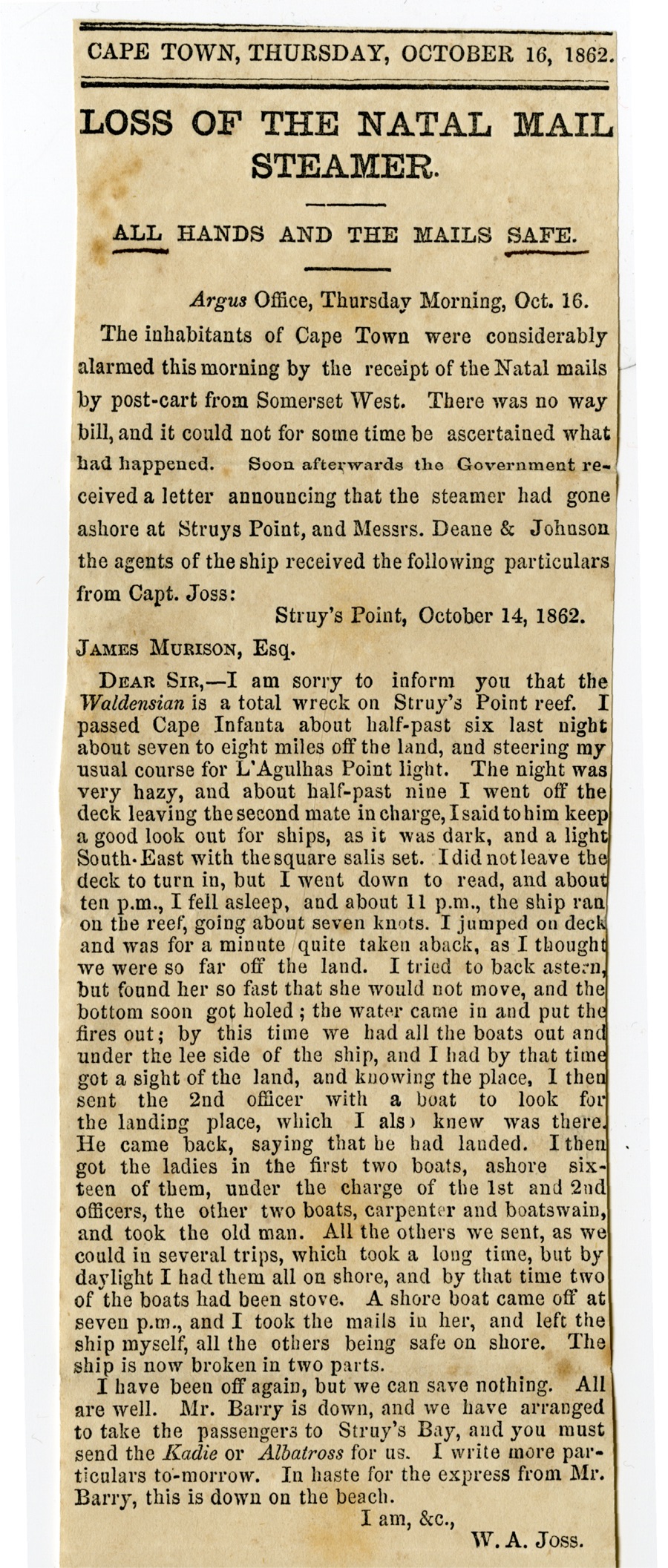

The wreck was reported widely across the British Empire. The Argus in Cape Town quoted the captain’s letter to the steam ships owner: I am sorry to inform you, he wrote, that the Waldensian is a total wreck …3

Our old friend “Waldensian” is no more, and with her has been lost the whole of the valuable cargo. Happily, all the passengers and crew were saved.4

Eye-witness accounts included that of an unnamed passenger, quoted in the Glasgow Daily Herald, giving a vivid description of the dark night, his heralding sense of foreboding, (even though he declared himself to be no believer in presentiments) and then the moment of impact:

…it must have been about ten minutes after 11 P.M.—the regular tripe sound of the engine, not unpleasant to one sleeping under the quarterdeck, was intruded upon and broken—never to be renewed—by the hoarse direful, crashing noise, which, in an instant told its own tale, and convinced us all of the danger that surrounded us.5

A detailed report was also published in the In the Inquirer and Commercial News where where the vaccine surgeon described the event at length, detailing his role in attending to the ‘ladies’ on the beach, gathering brushwood and lighting a signal fire, and noting the final fall of the mainmast at about ten or eleven o clock the following morning.

All the accounts exonerated the captain and referred to his exemplary conduct in saving the entire crew and all the passengers. Yet the blame had to lie somewhere. In a letter published in the Argus, the Rev. Mr. Naude, wrote:

The second mate had the watch, and cannot account for the disaster. He must (according to the opinion of several passengers) not have been looking out well at the time, for the vessel was very near the strand. The second mate must stand accused of indifference. The captain. who proved himself a very careful sailor, could not for a moment have thought of danger, else he would not have gone down in his cabin to read. Not the least can be adduced against his management or character on substantial grounds. Not the least blame can be attached to him. He stands exculpated in the mind of every honest man. The moment the vessel struck he was on the deck, and behaved most nobly. He was composed, energetic, and decided—prompt, and kind to the last.6

“Loss of the Natal Mail Steamer: All Hands and the Mails Safe.” The Argus, Cape Town Thursday, October 16, 1862.